Today we would have flown from London through Toronto to San Francisco, then BARTed to Pleasanton, then been picked up by some dear willing soul and ferried back to Modesto, either passed out in the back seat or so keyed up from travel caffeine that we couldn’t stop telling stories. The end. (And thus, today: the end of this #TheOtherCamino blog.) ** Today, the news that COVID-19 cases are spiking all over California has led to speculation that we’ll be sheltering in place again, that in fact the urge to reopen was premature, and our careless gatherings have proved that the virus never went anywhere—it was just waiting for us to let our guards down. I’ve been at home—minus some neighborhood walks, trips to the vet with a sick beagle, grocery runs, a trip to an abandoned airfield and an ill-advised recycling run where my tin cans netted me 23 cents—since March 12. Last week, my fall 2020 teaching schedule was confirmed, and it looks like I’ll be teaching my courses from home. I’ve gone through something like the stages of grief with this realization: denial, anger, bargaining, depression. I’m not quite to acceptance yet. Home isn’t just the place where I crash after a long day—it’s now the place where I put in the long day. I can relax here, but more and more, I’m trapped, too. My story isn’t special—this is happening all around my city, state and country. It’s happening all around the world. Sometimes it gives me comfort to think of so many of us at home, staring at our screens, trying to reach out to each other in little ways: a text, a meme, a thumbs up. Sometimes it depresses the hell out of me. ** Over the last 28 days, I’ve discovered new corners of my 1,000 square foot space: I write in the mornings at the kitchen table with the French doors open and my beagle wandering through, looking for a spot for his nap; I Zoom from my office with my bookshelves in the background; I read in the warm afternoons sprawled across the bed. I’ve been trying to do subtle improvements: a new dish drainer, new suction shower hooks, a basket system for Will’s rolled-up t-shirt collection. (This has been my biggest accomplishment of 2020, other than writing a blog for 28 days in a row.) I’m trying to make peace with my home, and with myself in this space. ** Yesterday, I opened the side gate and let two friends into my backyard. One I haven’t seen since February, although we text most days, little check-ins to remind each other that we’re alive and we care. The other friend I had only met on Zoom in a weekly writing group, but talking for an hour a week for three months has accelerated our relationship. We’re friends now, compatriots, kindred spirits. It’s been the unexpected joy of this pandemic. We sat in the backyard with coffee and tea, spaced apart, moving our chairs and the umbrella to avoid the sun. And it was hot. This was a commitment to friendship, to humanity. We were determined to sit six feet apart and just be together. This is all we have right now, and it has to be enough. ** If you’re reading this blog, thank you. Thinking in such a focused way about this walk, I’ve felt more attuned to the idea of the journey, and the people on the journey with me. We have each other, and that is enough. ** Since the beginning of 2019, when we started talking seriously about walking the Camino, Will and I (but especially Will, who’s quite good at this) have been seeking out other pilgrims who made the journey in previous years. We pumped them with questions, and they gave us their best advice: skip the meseta or stay in hotels every now and then or buy the right shoes. They told us what food was good and what food wasn’t, what kind of walking sticks we needed, whether we should continue on to Finisterre. Every single one of them said the trip was worth it, and most that they would do it again if they had the chance. Writing this blog has been bittersweet: it’s kept me adrift during this month of no other plans and at times heart-wrenching loneliness, but it’s also made me hunger for this trip. This is a journey I want to take someday, when the world rights itself. #Camino2021?

0 Comments

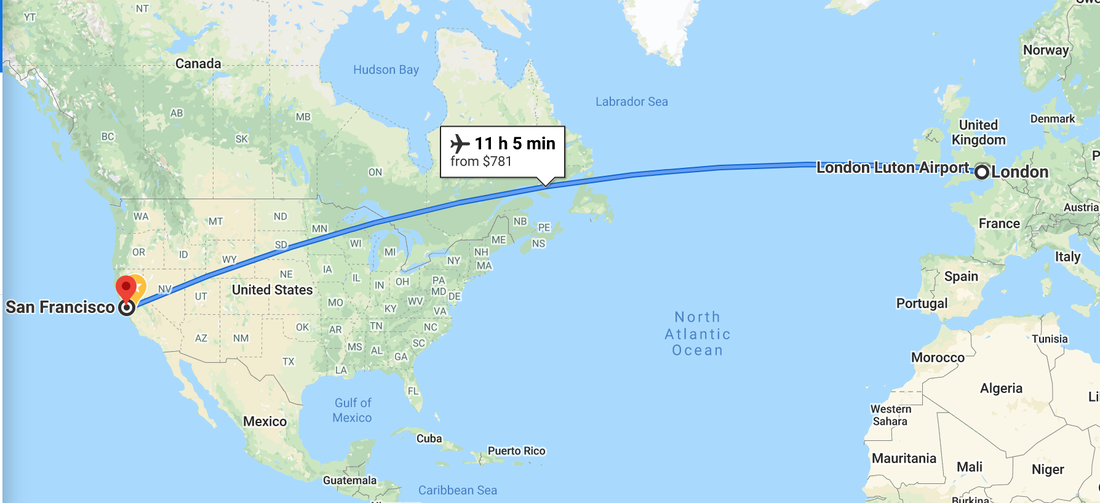

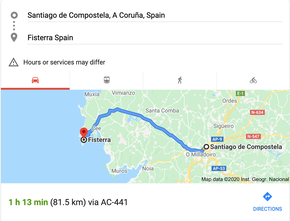

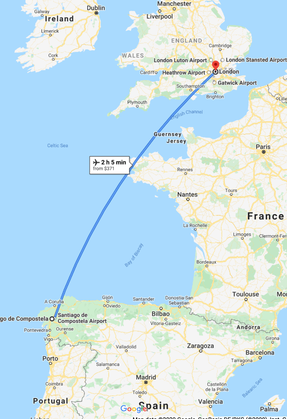

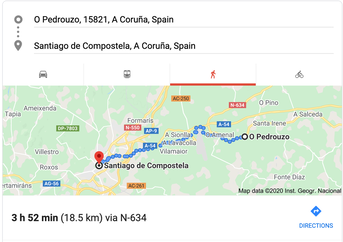

Santiago de Compostela to Finisterre and back (bus, 81km each way). Santiago de Compostela to London (plane, about 2,000 km). Many pilgrims leave Santiago de Compostela and do one last walk: to the Atlantic Ocean. Finisterre (from Latin finis terrae) was so named because in Roman times, it was considered to be the end of the known world. It’s a three-day walk, or roughly an hour by bus. There are three things pilgrims must do in Finisterre, according to Efren Gonzalez. (I’m linking his Finisterre vllog here, so you can watch it. We’re Efren Gonzalez fans around here. Fair to say, Will?) They are: -Take a dip in the ocean. -Burn something that’s been with you the whole way (like your clothes, or the underwear you washed every night in the sink for A MONTH). -Watch the sunset. Then, it’s said, the next day you’ll be a new person. ** We planned to do a quick trip to Finisterre by bus, then return to Santiago de Compostela for a flight to London, and then another flight the next day back to San Francisco. This would have been an end of the world/end of the journey kind of day. **  In that other, non-pandemic life where I would have been finishing the Camino with my husband and some of the best people we know in the world, this would have been day 27 without my dogs, the chaise lounge where I’m writing this, my laptop, cereal and television. I’m so firmly ensconced in my at-home world right now that it’s hard to imagine being gone long enough to miss it. These days, a trip to the grocery store still feels somewhat momentous, a little trepidatious. When I come back after thirty minutes, the dogs greet me like I’ve been gone for a week, and I feel compelled to report on the conditions, like I’ve been out on the front lines: “Hardly anyone in Winco at 9:30 p.m. on a Friday. Almost everyone wearing masks. Produce was pretty picked over, though…”. But if I had indeed been gone for 27 days, I would have driven my companions insane with my constant worries about my dogs—what they were doing, if they were happy, if LG was able to sleep without me, if LG was still eating her food, if they were already going crazy with pre-4th of July fireworks. Every single night, no matter how exhausted I was from the day’s walk, I would have had a difficult time falling asleep without LG’s nine-pound body tucked up against the back of my knees. I would have checked my email obsessively for mandatory dogsitter reports (I prefer the “proof of life” version with the dog holding the day’s newspaper). “The dogs are fine,” Will would have told me, approximately twenty-seven times a day. And twenty-seven times a day, I would have sniffed back some tears. ** Coming back from anywhere always seems to take twice as long as getting there in the first place. I’m not sure how much of this Will and I shared with our Camino traveling companions in advance, when we were planning our trip and buying our plane tickets, but he and I have had some uniquely bad experiences with air travel. We were once denied entry to a flight that our luggage had already been booked on; that was also the night we slept under a café table at Heathrow. We’ve had missed flights and delayed flights and rearranged plans—and it’s all fine, really. It’s part of the adventure. It’s just not that much fun when you’re exhausted, when you haven’t had a really good bath/shower in a month, and when you’re sick to death of the two clothing options in your backpack. About a decade ago, I chaperoned a school trip to Washington D.C. and New York: twenty-two 7th and 8th graders, me and my colleague Tu. During this week, I don’t think I got more than six hours of sleep a day, and each day was nonstop go-go-go. In the last twenty-four hours of the trip, we bused from DC to New York, walked all over Manhattan, went to a Broadway show, bused back to Brooklyn for only five hours of sleep, had an early breakfast, wandered around Ellis Island, and got on a plane. The second after I counted and double-counted and triple-counted to make sure everyone was on board, I buckled myself into my seat, leaned my head against the seat ahead of me, and fell into a dreamless sleep. The next thing I remember, it was six hours later, and Tu was shaking my arm and telling me we were landing soon. I’d slept through takeoff, food service, in-flight entertainment, and turbulence. And my neck was killing me. ** In 2002, after our month-long trip around Europe, we were beyond ready to be home, but we had to make our way back to Paris. Our last stop before the final train was in Zurich, and we had a few hours to kill before our train. “What do you feel like eating?” Will asked. The appropriate answer would have been fondue, or some sort of Swiss delicacy. Anything that you wouldn’t get in the States: that’s our rule when traveling. But the answer that shot out of my mouth was, “McDonalds.” And so, we ate that night in a three-story McDonalds with the most modern seating I’ve ever seen in a McDonalds, the whole restaurant pulsing with techno music. It wasn’t bad food; it had the requisite salt and fat contents to make it taste quite good. But the point, right then, was comfort. The point was that we wanted to be home, that we missed even the crappier aspects of home. It’s good to set out on a journey, but it’s also good to return. And that’s tomorrow.  The final stage of the Camino Frances is from O Pedrouzo to Santiago de Compostela. At 19.7km, it’s one of the shortest days on the route; because it’s the last stage, headed toward the place where all the pilgrims are converging, it’s the most crowded part of the walk. For those who started in St. Jean Pied de Port and walked straight through, it’s been a 775km (481 mile) journey. Those who skipped the meseta (that would be my group) were looking at 482km (299 miles). Either way: that’s a hell of a long walk. Santiago de Compostela is the (disputed) site of the tomb of St. James (yep—the apostle James from the New Testament). Since the Middle Ages, pilgrims have been traveling (on foot, mostly) to visit the Catedral de Santiago de Compostela. With its baroque façade and Romanesque bell towers, it’s impressive even if you aren’t Catholic, and even after you’ve passed roughly a hundred churches along the way. Upon arrival, travelers queue outside the pilgrim office to get their official Compostela, the certificate that proves the pilgrimage happened—something that will presumably last longer than blisters and sore muscles. Maybe even longer than a blog post. Buen Camino, the typical greeting of pilgrims on the trail, translates to good road or good path. It’s an acknowledgement of a shared sense of purpose, an understanding and respect for another person’s journey.

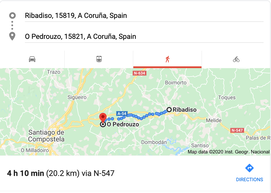

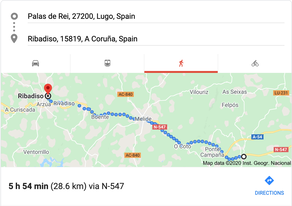

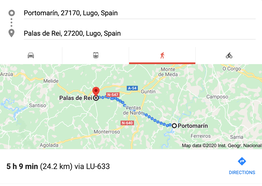

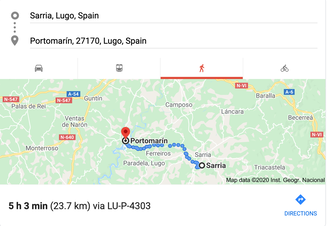

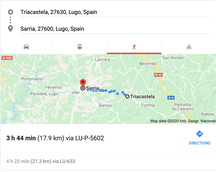

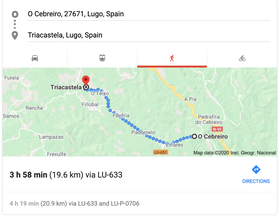

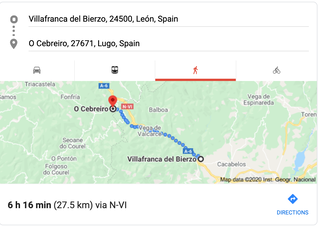

The last time I was in Spain (which is a funny way to say it, as if I’m in Spain all the time)—we went to Pamplona and Will did the encierro, the running with the bulls. There’s a traditional costume for the run—a white shirt, white pants, a red scarf around the waist and a red handkerchief around the neck. (The white represents San Fermin’s purity; the red represents his death by decapitation. You don’t have to dig far into tradition to find the blood and gore.) The streets are full of runners in these costumes; the clothing marks them, gives them a sense of camaraderie. After his run, when his head was so inflated he had to duck through the doorways, Will was part of this group. His heart was still pumping overtime, adrenaline not yet settled. Every time we passed another person in white and red, they acknowledged each other with a solemn nod. Solidarity. We survived. ** Santiago is lively: here’s where you meet up with the people you passed along the way, where you get your Camino souvenirs and (ill-advised?) scallop-shell tattoos. There’s a guy playing bagpipes in the cathedral passageway. Many people stay in the Parador, a famed five-star hotel—a definite luxury after bunkbeds and communal living. (“Would we have stayed in the Parador?” I asked Will. He laughed. “I can tell you damn well we wouldn’t be staying in an albergue.”) There’s something celebratory about being in Santiago de Compostela, for sure—but also, something bittersweet. It’s the end of one journey, the beginning of another. ** If the walk changes you, then who are you at the end? What will you do with yourself? How will you take your changed self back to the real world? The truth is, writing this blog has more or less saved me from a deep Camino-shaped depression. Back in March when the pandemic hit and shelter in place became mandatory, I threw all my focus into figuring out remote teaching. I had to rethink some curriculum, learn different ways to deliver information, and stop teaching at times to be a counselor, a cheerleader, a person in my students’ lives who cared. While the Internet was full of witty memes and suggestions about how to spend the time in quarantine—I was swamped, so tired some nights that I dragged myself to bed before ten. And then, abruptly, the semester ended the first week of May. I did my grading. I cleaned the house. I tackled a few neglected projects. I kept moving to keep the weight of the trip I wasn’t going to be taking from settling onto my chest, like an X-ray apron. The summer of doing nothing and seeing just about no one, trapped mostly in my house during long strings of one hundred plus days loomed on the horizon, an unbearable possibility. “I think I might do a little blog about our trip,” I told Will. “What trip?” “The one we’re not taking.” “Huh,” he said. ** I don’t do a lot of personal writing. (Or I do, but it’s disguised as fiction.) My own life has never struck me as particularly interesting—just comfortable—and I worried that I wouldn’t have the material to keep this going. No problem, I thought. I’ll write about our pets. I’ll write about Will. I’ll write about the Camino itself. It’s been like a little puzzle to figure out every day, finding the edges and corners, filling in the middle. It has been its own kind of journey. ** It’s said that the walk changes you, but I think it must also be true that the walk changes everyone in a different way. That’s another mantra of the Camino: no two Caminos are ever the same. Put another way: everyone walks their own Camino.  Ribadiso da Baixo to O Pedrouzo is a 20km walk—the second to last day of the Camino. Leaving Ribadiso, pilgrims walk along an old country road to Arzua: pastureland, cows, farmhouses. Along the way to O Pedrouzo, they can stop to smell the eucalyptus forest straight out of Lord of the Rings. (Not really: it just looks that way in pictures.) This is the last day of the routine that began 23 days ago in St. Jean Pied de Port; the last day of the new normal. ** Life on the Camino has a particular routine, determined by how far one is walking that day and what time they need to check in at an albergue. Here’s how I imagine our days would have been: 5am(ish): Wake in the dark. Change into walking clothes—or better yet, sleep in them so you’re ready to go. Roll up your sleep sack, put on your hat, grab your walking poles, sling your backpack over your shoulder and be out the door. (There is no fixing hair. There is no need to look in a mirror.) 7am(ish): After a couple hours of walking, stop for first breakfast—coffee and a pastry. Walk, alone or with others. 10am(ish): Second breakfast. Something a bit heartier. Walk, alone or with others. Noon(ish): Lunch. (Or wait until destination, depending.) Walk, alone or with others. 1-2 pm: Arrive at destination. Find your bed at the albergue, which ideally you reserved the day before. Shower. Wash clothes (in the sink, in the washer, or in the shower, depending.) Hang wet clothes to dry. Or: Stay in a hotel. It’s not that much more expensive, and it’s an option if you want a better night’s sleep and a bit more privacy. 4pm: Siesta: everything is closed. Chill and read a book. Or blog. Or post videos. Or sleep. 7pm: Dinner—usually the pilgrim’s meal, or a meal of the day, eaten in community. (A starter (salad), a protein (beef or fish) and starch, dessert and either beer or wine. After several days of a pilgrim’s meal in a row, it will begin to feel a bit monotonous.) Talk. Meet people. Share histories. 10pm: Albergues close, and you have to be in for the night. They’re run by the church and the municipality, so they’re clean but sparse. This is dormitory living, sleeping in bunkbeds. This is respecting the needs and space of the people around you, while trying to carve out your own tiny niche. Read by light of the Kindle. Sleep. ** Every day for this blog, I’ve used google maps to chart the path from town to town. Google’s default is to travel by car; the algorithm simply doesn’t assume that one will be crossing a country on foot. Today’s walk—straight through, no stops—was estimated at four hours, ten minutes. It would only take 22 minutes to make the drive. To some people, I understand, this makes absolutely no sense. And for most of life, I agree: the point is to get there faster, without a lot of fuss. But the point of the Camino is simplicity. Getting down to basics, spending the time in your head, searching your heart. For many, the Camino is a religious pilgrimage to the tomb of St. James at the cathedral in Santiago de Compostela. There are churches along the route, daily masses for pilgrims. I’m not Catholic, but it doesn’t seem like it would be that difficult to get into it, to see the journey as not just one of the body and the mind but of the spirit. This is the pilgrim mindset: we’re on a journey through life. ** Pilgrims on the Camino have a particular greeting: Ultreya! (Also: ultreia.) It translates to “Onward!” or “Persevere!” and also functions as a salute, given in solidarity. I am not, today, where I planned to be on my journey. I thought I would be near the end of my trip to Spain, the hard-won miles behind me, a kind of clarity opening up in my mind: this is what I should do, this is how I should be. This last year has been rough for me, even before the pandemic. I’ve questioned choices, ended relationships, wrestled at night when I should be sleeping with big questions. Maybe it’s just being 44 and feeling restless—the midlife crisis that in theory I should be able to squash with a flashier car. Up until this point, I’ve always been pretty good at glimpsing around the corner to see what’s coming, but that’s been elusive lately. I don’t know what’s coming or how to plan for it. I don’t see the next possibility, the next opportunity. I’ve been feeling stuck. The Camino, I thought, would unstick me. In the many blog posts I’ve read about the Camino, this is a common theme: the Camino changes you. It stays with you, long after you’ve returned to your house, your job. For many pilgrims, this isn’t a one-and-done. They come back, walking a different route, or another section of a route, again. They stop at their favorite albergues, talk to their favorite innkeepers, try to get back to that moment when everything felt so clear. I wanted to be changed. But I have to believe it can still happen, in some other, different, unexpected way. Onward.  Palas de Rei to Ribadiso de Baixo (25.6km/16 miles) is a walk through the province of Galicia—white wine country, known for its el pulpo (octopus) and torta de Santiago (almond cake)—which has a heavily Celtic cultural influence dating to the 5th century. The countryside is dotted with horreos, raised wood or stone structures on pillars that used to house grain. The towns are small, the landscape rural. Ribadiso is not even a village—just an albergue surrounded by fields. This stage of the journey is marked by heavy crowds. At this point, we would have been two days from Santiago and four days from home. At this point, I’m four days from finishing my blog. ** We’ve been doing a little project at Casa de DeBoard—a landscaping design for our front yard, which we’ve been mostly ignoring for the better part of seventeen years. It has a rose bush I’d like to pull out, some non-exciting shrubs, a box hedge, and a large weed patch that we call a lawn and have faithfully watered and mowed just so the neighbors don’t hate us. The new plan calls for us to rip out all the grass (… goodbye, weed patch!) and put in stones, bark, and drought-resistant native plants, meant to grow in ridiculously hot and mostly arid climates. The process has revealed how very little I know about plants, but it’s been interesting, too—each plant I google has a history, can be traced back to so and so’s arrival in the New World. It’s funny to think of plants being carted halfway around the world, how the colonizers really just wanted to pick up the Old World and move it with them to their new place, like they were loading up a U-Haul and carting things across town. Maybe wherever we go, we want to protect ourselves from change. ** I like to think that the people who walk the Camino—a spiritual walk, following ancient paths—are well-intentioned, that they leave light footprints on the places they have visited and come away changed by the experience. But I’m on some Camino Facebook groups, and I see complaints about people leaving behind their trash on the walk—notably, toilet paper—but other things, too. There are people who bus their way through the Camino, stopping in small villages for stamps in their passports and overrunning local cafes before getting back on the bus. And then there are the complaints from disgruntled travelers: about the owners of albergues, the quality of the pilgrim meals, all the little things that didn’t meet their expectations. ** I wonder what it would be like to live and work along the Camino route, to come into daily encounters with pilgrims—weary and crabby and overwhelmed or loud and festive and obnoxious. Like any tourist-centric economy, people make their living from the pilgrims who pay to stay at the albergues, eat their food for first or second breakfast, make demands to arrive late and leave early and be accommodated at all hours. There is a sense of entitlement that sneaks along, packed into a tiny pocket: I arrived late at the albergue and the owner was grumpy and didn’t want to let me in! Well, duh. I suppose the owner wanted some sleep, too. I have been, as a traveler, hyper-aware that the people who serve my food couldn’t afford to eat in the same restaurant. (I know I don’t have to travel outside of my city to experience this.) I’m aware that there’s a role I’m playing: the entitled traveler, but also the person who is pumping money into the system that allows my server to pay their bills, feed their family. It’s not an easy balance. ** A few days ago at the grocery store, the woman behind the register thanked me for wearing a mask. She was wearing one, too—for an eight-hour shift, presumably, while I was just dashing in for… and here I will sound like the most entitled person in the world: a cup of quinoa needed for my turkey meatloaf. “It’s not a big deal,” I said. She smiled at me—yes, you can see that, even in a mask. The mask means you have to look a bit closer, actually look people in the eyes to have an interaction. “For some people,” she said softly, glancing around the store, “it seems to be.” This has become, weirdly, a dividing line in society. It seems like such a strange hill to die on (maybe literally). In the past, I didn’t think much about the little droplets of air expelled each time I breathe or talk or laugh, but these days I imagine them landing on the arm of elderly person, on the gallon of milk that will be picked up by a young parent and brought home. If we can tread lightly, I think we should. It’s not a difficult way to exist in the world.  Portomarín to Palas de Rei (24.3km) crosses the Ligonde mountain range, which includes an ascent to Mt. San Antonio and a misty descent through the valley. Throughout the Camino, the walkway for pilgrims is marked by yellow arrows, but as I was reading through some blogs on this stage of the journey, I learned that it’s possible to miss an arrow and therefore make a wrong turn, which means backtracking, lost time, a longer day. The Camino de Santiago has an official symbol—a scallop shell—which can be found everywhere along the journey and is often taken home on souvenirs. The scallop shell is a reference to the Atlantic Ocean—the end of the earth. Although the walk officially ends in Santiago de Compostela, Finisterre (the end of the known world, at the time people started making this pilgrimage) is another three days’ walk or a short bus ride away. (Among our group, there was talk of a scallop shell tattoo that was never fully scuttled. Does my non-walk walk earn me a tattoo at one of Modesto’s fine establishments?) Road signs are emblazoned with the scallop shell; it’s painted on buildings and fences and walkways. Still, apparently, it’s possible to get lost. ** In the months leading up to the Camino, when I had things to worry about other than a global pandemic, this was the kind of thing I worried about: getting lost on the Camino. Also: my knee dislocating (again), blisters, bathrooms that wouldn’t be entirely private, and not sleeping. But mostly: getting lost. Some people are born with a sense of direction—it’s innate, not taught by a map or an app. Will has this; I’m convinced you could drop him blindfolded from a plane and provided he survived the landing, he’d be able to walk his way home without looking at his phone or stopping to ask for directions. I was not born with this skill. It may seem like an exaggeration to say this, like I’m making my directionally challenged self sound more directionally challenged to get to some kind of punch line. But no. What I’m about to tell you is true. ** When I started teaching at UC Merced, I met a friend who didn’t have a car and used the Cat Tracks public trans system, which is free and reliable although not necessarily convenient. I was happy to drop her off at home on my way from campus to the freeway—although it was a slightly different route than I normally took. And herein was the problem: every single time, she had to remind me where to turn, what lane to get into, when I’d passed the final turn onto her street. Every. Single. Time. It’s become a bit of a joke, but still, even as we’re laughing about it, she has to insert a quiet, “Turn left here.” ** I don’t always know where I am, but if I do it’s because I’ve memorized the route to get there. Google Maps and its predecessors have made most travel painless; I don’t even have to think, just follow orders. Sometimes it goes on the fritz, though—a lost signal, or a sudden roadblock that causes me to backtrack, reroute. In my late twenties and early thirties I wrote for a real estate publication—this was before the housing crash in 2009. The job was easy and mostly fun, except that when I was asked to write about a new housing development, it was often in some new area with street names that hadn’t yet made it onto maps. I spent a lot of time turning the wrong way, realizing, circling and eventually figuring it out. The photographer was usually there when I arrived, and sometimes nearly finished. In those few minutes when I was lost—it was never more than a few minutes, although that time somehow managed to feel like hours—I had what I now know was a panic attack. My heart seized; tears welled behind my eyes; it was difficult to breathe. Sometimes there was a person around to ask for directions, but mostly, I had to talk myself into trying again: you can do this. There’s no reason to panic. You’ve always figured it out before, and everything has worked out fine. I rerouted, tried again, and always survived. ** I’m writing this at night, with an episode of The West Wing on TV and my husband on the couch next to me. “I need more examples,” I told him. “I can’t remember specific times I got lost, except every single time I’ve been in a hotel and I’ve turned the wrong way coming out of the elevator.” “Well, there was Venice,” he said, not missing a beat. Right. Venice. I was so disoriented at the lack of trees and the winding pathways between three story buildings, I wandered for an extra hour with my heavy backpack before finding the hotel, just off St. Mark’s Square. “And then there was the corn maze,” he reminded me. It’s true. I once got lost in a corn maze and had a panic attack. I was 32. And then he said, “Most of the time you’re with me, so it’s hard to get lost.” ** Today I used GPS to get me to a Rock and Ready Mix place five minutes from my house. There’s no telling what would have happened to me on the Camino, with my #CaminoAmigos inevitably walking ahead, at a faster pace. I would have had to watch for the scallop shells, follow signs, be alert. I would have had to trust that I could figure it out—eventually.  As this is the last stage of the Camino Frances—the last 100km before Santiago de Compostela—the route is much busier. There’s plenty of food, water and shelter, so long as you book ahead. The route passes through 21 villages from Sarria to Portomarín (21.9km), oak groves and Romanesque building remains. There’s a gorgeous medieval bridge over the Miño River into Portomarín. What I loved was this bit of trivia: When the Belesear Reservoir was built in the 1960s, the old town of Portomarín was flooded. In order to preserve the ancient structures, they were dissembled, moved stone by stone and reconstructed in the new town. This is a damn good metaphor—for what, I don’t know yet. ** Yesterday, on my non-walk walk, I got sick. It started on Saturday night around 9 p.m. I was reading There There by Tommy Orange which was fantastic, and I decided to push through and finish the last 50 pages. And then a weird thing happened (weird considering a day with very little physical activity and an hour-long afternoon nap to boot): I got so drowsy so fast that I could hardly lift my head. I couldn’t even turn a page. Covid, of course, has me on edge. Back in March, it was not possible to cough without worrying if this was it. (As the memes say: Is that you, Rona?) At the time, I memorized the lists of symptoms and performed a sort of mental check each day: no cough, no fever or chills, no body aches, no difficulty breathing, no fatigue, no headache. Still: blow my nose, worry. Wake up in a sweat (probably due to being a 44yo woman in a blistering not-quite summer); worry. ** Saturday, I fell into an early sleep and woke Sunday with a screaming headache. I get maybe one or two headaches a year, at times when my coffee supply has run low or some unspeakable tragedy has prevented me from having coffee. But this headache was different—something pulsing behind my temples, sloshing in my head when I tried to get to my feet. I held onto the walls to get down the hallway; I tried to pretend everything was normal and so washed down ibuprofen with my coffee, wrote about 600 words in two hours (not a good ratio for me), walked the dogs, took my temperature (98.6) and practically crawled back into bed. Where I slept for another five hours. ** It’s Monday now, and this weird day of drowsiness seems to be behind me. I feel if not 100% then a good 85%, but it’s only 6 a.m. and as I’m writing this I’ve had exactly two sips of my first cup of coffee. In other words, I usually feel 85% at this time. Also, a better sign of recovery: I woke up to see that the house was filthy. The other person who lives with me (he who may or may not be reading this blog) had left various shirts draped over various pieces of furniture—where he was standing, apparently, when he got hot. There was a heap of dishes in the sink, crumbs scattered over the counters and tabletop, a little pile of recycling that hadn’t made it to the bigger pile of recycling in the garage. Noticing that things are out of order and feeling like I have the energy to do something about it is a sure sign of recovery. So, what was that? A mini-Covid, mild as it comes? A bad case of allergies? My body telling me I’d earned a day off, whether I wanted it or not? I really couldn’t say. ** At this stage of the journey, pilgrims are tired. There are hundreds of kilometers behind them, but by the time they reach Portomarin, only 80 or so kilometers to go. In the few races I’ve run, pre-knee injuries, this is the hardest stretch. The initial burst of energy is gone and the final burst, the one that propels a runner across the finish line, isn’t here yet. This is where stamina comes in, willpower, the refusal to give up and sit down and have a good little cry. This is the stage to honor the body—thank you, Yoga with Adriene—to feel all the little bumps and bruises and blisters and appreciate them for what they mean. We’ve come this far. We can make it just a bit farther. ** Note to self: you’re not invincible. Injuries can happen when you’re not careful (they can even happen when you are). If your body is telling you something, slow down and listen. And also: Wear the damn mask.  There are many routes to Santiago de Compostela—but notably, the French Way, which starts in St. Jean Pied de Port, France (764km), the Portuguese Way, which starts in Lisbon (620km), and the Northern Way, which begins in Irún (824km). But there are people who begin their walks from all over Europe and hit one of these routes; it only takes a Google search to find people who have been walking for six months or more. Six months. Walking. Not many people have six months—or a month, at their disposal. Many pilgrims do the Camino in stages—a week here one year, another week the next, until they’ve chipped away at the pieces and walked the whole route in a lifetime. Along the journey, pilgrims get stamps in their Camino passport; in Santiago de Compostela, pilgrims get their official Camino document certifying their journey (the “Compostela”) if they have walked the Camino for religious or spiritual reasons, and if they have completed at least 100 km on an official route. On the French Way, that 100km mark begins in Sarria; Triacastela to Sarria (21.9 km) would have been the last leg of the trip without huge crowds. ** Does a piece of paper—like the Compostela—really mean anything? Our group said yes; we wanted to get the certificate. I’ve acquired other pieces of paper in my lifetime, some of which I’ve faithfully retained, others of which have disappeared. I have several diplomas, and right now I have only a vague idea of where they are (a box high in my office closet?). Last week, for my visit to the DMV, I had to get my paperwork in order: birth certificate, marriage license, SSN, documents that prove I live at my address. This caused no small amount of anxiety because although I’ve had my SSN memorized since I was sixteen, the card itself was more elusive. After searching old wallets and my “official docs” folder to no avail, I upended my nightstand drawer, which needs a good decluttering, and found it there. I have no memory of putting it there, and no idea why I thought this—amidst old gift cards I never used and wallet-sized photos of my nieces and nephews—would be a secure location. As a citizen, it’s a special kind of privilege to not have to think about documentation. The social security card came to me through no great difficulty: I was born here, and at some point I asked for it. The birth certificate I presented at the DMV wasn’t the original (I’d been careless there, too, bringing it with me to college and probably tossing it out when I moved) but a certified copy that the attendant reviewed skeptically before allowing me to pass. I was there in the first place because my license had expired during the pandemic closures, and I’d been given a grace period to figure it all out. It was humbling, for a very small moment, to have to prove who I was and that I deserved to be here. And appropriate, in a week where the Supreme Court defended DACA, to think about how much a piece of paper might influence one’s destiny. ** When I travel, I wear a money belt tight and low around my hips, my passport, credit card and any cash tucked inside there. I follow the rule of never leave anything important in the hotel. This was tested once when we had a 11 a.m. checkout from our hotel in Rome and returned from a visit to the catacombs at about 11:10 a.m. to find our belongings in the trash. (No problem—we dug them out and went on our smelly way.) And I also follow another rule: never put anything important in your backpack. Once, waiting for a bus in Barcelona, someone unzipped my backpack and went through it while I stood there oblivious, alerted only when the bus driver stepped in, yelling at the thief. My backpack held only a map, sunscreen, and a water bottle, all of which were still intact. Another time: Will and I were on a night train from Zurich to Paris, dozing uncomfortably in our bunks with our backpacks tight around our limbs so they couldn’t be pulled away when we slept. Suddenly, the door to our compartment opened and there were uniformed men with flashlights and German shepherds barking orders to us. Passports! Present your passports! It was like we’d fallen asleep and woken up in Nazi-occupied territory. Wordlessly, we dug in our money belts, handed over our passports, and stared at each other. Now what? We’d spent weeks guarding our passports with our lives, only to hand them over to the first people who demanded them. What exactly would we do if we arrived in Paris for our flight back to San Francisco with no documentation? How did one get a new passport—at the embassy? How long did this take? How did we prove who we were without the appropriate paperwork? It wasn’t until we crossed a border at some point the next morning that our passports were returned to us, and we finally felt safe again. Apparently, it was part of the process—an identification check—and not some kind of anomaly. We hadn’t been signaled out; everyone else in every other compartment had had the same rough awakening. Still—it took a while for my heart rate to get back to normal. ** After walking 764km to Santiago de Compostela—minus the meseta, of course—I would stand in line for an official piece of paper, fold it carefully and tuck it into my backpack, and someday not be able to tell you where exactly it was—a box high in my closet? A pilgrimage is meant to be spiritual, a mark on the heart.  The walk from O Cebreiro to Triacastela (19.6 km; a nice “light” day) is a zigzagging descent down a mountain and through the valley, with panoramic vistas of pastureland and small villages. This portion of the walk contains one of the Camino’s iconic statues: a bronze pilgrim, leaning into the wind. ** The descent, of course, is much easier than the ascent. Or at least, in theory this is true. During and after the ascent, it’s the muscles that are sore, that demand ibuprofen (or even better, the pain patches you can buy along the route of the Camino, which aren’t yet available in the US). On the descent, it’s the joints—the hips, the knees. This is where things can go wrong. ** Yesterday was a mini-emotional rollercoaster. The day began with a three-and-a-half hour visit with a dear friend. We’ve chatted over Zoom a couple times but haven’t seen each other since the pandemic began, and so: coffee, talk about life and teaching and truncated plans and coffee, tears, talking. My heartbeat did this weird uptick just to be out in the world, entering through her gate, fending off her tiny loveable dog. It’s been hard to find these moments. Then, it was a rush home and another rush across town with Will, Baxter in his crate and LG on my lap for Baxter’s vet appointment. LG is smarter than she looks; she has no problem being left with Baxter but refuses to be left on her own. For his part, Baxter has a 15-year-record of horrible behavior at the vet. While we waited for our appointment—Will and LG outside, since only one of us could come in due to pandemic restrictions—Baxter circled the lobby and then the exam room approximately one thousand times, which meant doing a thousand mini-hurdles over the bar under the exam table. Every time someone opened the door, he tried to make a run for it—which was ironic, considering that his largest issue at this stage of life is his mobility. It was a strange discussion, because at times we talked about treating him as if he had all the time in the world left—as if we were talking about some spry ten- or twelve-year-old. And also, we had the talk about what happens then, because it’s coming, and we all need to be prepared. While the vet talked calmly, I sobbed into my mask in the exam room and Will cried in the parking lot, and Baxter circled, circled, hurdled the bar under the table, circled. At home we fell into an exhausted sleep, all four in different corners of the house. I had that feeling on waking that I’d slept through an entire day, that somehow it was the next day already and I’d missed my morning appointment. I looked at the clock: thirty-five minutes had passed. After another mini-nap, I woke in high-bitch mode, my default after unsatisfying naps. It wasn’t the best state of mind to log on Zoom and chat with the Friday night anti-racist book group I joined a few weeks earlier. We’re three weeks into a discussion of White Fragility and it’s powerful to see people making realizations, owning and acknowledging. There’s a scrubbed-raw feeling that comes with this, a bit like running your heart over a mandoline. And yet, every time: hope. And then: unwinding. I tried to settle into a rerun of The West Wing, which is hard now, too, considering. It almost feels like a fairy tale, some bedtime story of a forgotten land. This is how government should work, kids. In the midst of this: fireworks. We’ve been hearing them for more than a week now: sudden booms that shake the house and sometimes feel far too close, or distant crackles like static electricity. One of the benefits of being a fifteen-year-old somewhat placid beagle (especially after the one thousand laps) is that you can sleep through anything. But our ready-to-fight ten-year-old rat terrier hears all, and so: an hour of trying to calm her rapid heart, the realization that we are still fifteen days from July 4. And then, a ping on my phone as I was settling into bed, into the breeze from a fan blowing in the window. An out-of-the-blue thank you from a student: thank you for encouraging me. [Cue heart-swelling music.] ** I’ve been trying to come up with a theme for each day, for the walk (or the non-walk walk, as I’ve begun to think of it), and each day the theme somehow suggests itself. But today all I can think of is, keep going. Keep moving. There is still good out there. There are people who care. Keep putting one foot in front of another. The walk was never supposed to be easy.  Today would have marked the 2/3 point of our journey: a steady, sweaty climb from Villafranca del Bierzo to O Cebreiro, at just about 30 km (18 miles). The ninth century stone village of O Cebreiro is “an impossibly quaint hobbit hamlet” that “smells like wood fires, manure and pilgrim B.O,” according to Rick Steves (who in 20 years of travel has never steered me wrong). At this point, pilgrims have exited Leon and entered Galicia, encountering another new language: Galego, a mixture of Spanish and Portuguese. There are seven more days until Santiago de Compostela; a good part of the journey behind, and a good ways to go. I read some blog posts from other pilgrims about today’s journey, and one woman described utter exhaustion setting in only halfway through the route: every time she saw a town in the distance, she thought it was O Cebreiro. It had to be; she’d been walking forever; she had nothing left. But it wasn’t, and she had no choice but to keep going. There’s no way to know what your own journey will be like, even with a roadmap. ** Sometimes when I look back on the person I am today, versus the person I was five years ago or ten or definitely twenty, twenty-five years ago—I don’t recognize the older versions of me. Things are about to get personal here. This is your warning to leave. ** For a long time, I allowed other people to define things for me—and that included defining me, who I was, what I could do. I was in my thirties when I raised my voice for the first time (not literally; but almost literally), when I thought that I might have something to say that was worth the effort, when I broke free from the things that had been holding me back. I’m talking vaguely. I can circle a topic for hours; watch out. How to say this? I grew up in a community where a woman’s highest calling was to be a mother. No problem. I figured that was coming down the road for me at some point. I had a mother. The women I knew were all mothers. It was so expected it was taken for granted; women who didn’t have children were anomalies, oddities, eccentrics. And then, when I was 13 and experiencing such heavy cramps and bleeding I was in the doctor’s office repeatedly, I first heard the word ‘infertility’ mentioned in connection with me. The doctor said the word to my mother, maybe judging that I wouldn’t know what it meant or that I was too young to be part of the conversation. But I knew the church-word for this: barren. It was never once presented as a positive thing for a person to be. Over the years, despite medications and painkillers and lost days each month and thousands of dollars in emergency care bills, my condition grew worse, and when I was 22, I had an operation that made infertility no longer a possibility but a fact. For a decade, I drifted. I went to everyone’s baby showers. I learned how to knit an eight-hour baby blanket (--full disclosure: it takes me twice as long, but that’s the name of the design.) I spent my time around people whose conversations revolved around their children’s milestones, parenting techniques, homeschooling. It was in many ways a loving and generous environment, but the span of the communal embrace wasn’t wide enough to include me. I don’t mean this as an indictment of anyone else’s behavior. When I look back on those years, I see myself as the outsider who just didn’t have the guts to get out. It was hard to fit into the group. I had to use my elbows to claim a little space, and it exhausted me. I kept doing: knitting, baking, trying to find my way to that common experience. But I had different interests, different ideas. I was teaching, I was reading, I was studying. Looking back, I’m sure I exhausted them, too. It wasn’t until I went to grad school that I finally made my exit from the circle. In a way, it was terrifying. Those were the people I knew and loved, even if we didn’t understand each other, even if we had different vocabularies. I didn’t know where I belonged, who I was when I wasn’t trying to camouflage myself. But also, of course, it was a relief. I became a person who wasn’t defined by a deficit, but by the qualities I did have and the things I could do. The process of becoming, like leaving the cocoon, has to be painful and terrifying at times—otherwise, you haven’t really come that far. ** In many ways, I’m the latest of the late bloomers. It took me a long time to figure out who I wasn’t, and then who I was. It took me a long time to learn that I could speak, that I had a right to speak, and that maybe there was even some value in what I wanted to say. It’s so funny to me that as a teacher, I feel I can recognize this in students so easily, this thing I couldn’t recognize in myself for so long. Here’s a person who needs a little nudge. Here’s a person who is afraid. Here is a person who might need a word of encouragement to start on this path. ** How long did it take you to write your first book? I’m sometimes asked. There are practical answers, like a year of the first draft, another six months for a second, other revisions at later points. But also, a more honest one: 37 years. |

Paula Treick DeBoardJust me. Archives

December 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed