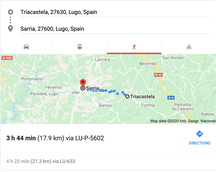

There are many routes to Santiago de Compostela—but notably, the French Way, which starts in St. Jean Pied de Port, France (764km), the Portuguese Way, which starts in Lisbon (620km), and the Northern Way, which begins in Irún (824km). But there are people who begin their walks from all over Europe and hit one of these routes; it only takes a Google search to find people who have been walking for six months or more. Six months. Walking. Not many people have six months—or a month, at their disposal. Many pilgrims do the Camino in stages—a week here one year, another week the next, until they’ve chipped away at the pieces and walked the whole route in a lifetime. Along the journey, pilgrims get stamps in their Camino passport; in Santiago de Compostela, pilgrims get their official Camino document certifying their journey (the “Compostela”) if they have walked the Camino for religious or spiritual reasons, and if they have completed at least 100 km on an official route. On the French Way, that 100km mark begins in Sarria; Triacastela to Sarria (21.9 km) would have been the last leg of the trip without huge crowds. ** Does a piece of paper—like the Compostela—really mean anything? Our group said yes; we wanted to get the certificate. I’ve acquired other pieces of paper in my lifetime, some of which I’ve faithfully retained, others of which have disappeared. I have several diplomas, and right now I have only a vague idea of where they are (a box high in my office closet?). Last week, for my visit to the DMV, I had to get my paperwork in order: birth certificate, marriage license, SSN, documents that prove I live at my address. This caused no small amount of anxiety because although I’ve had my SSN memorized since I was sixteen, the card itself was more elusive. After searching old wallets and my “official docs” folder to no avail, I upended my nightstand drawer, which needs a good decluttering, and found it there. I have no memory of putting it there, and no idea why I thought this—amidst old gift cards I never used and wallet-sized photos of my nieces and nephews—would be a secure location. As a citizen, it’s a special kind of privilege to not have to think about documentation. The social security card came to me through no great difficulty: I was born here, and at some point I asked for it. The birth certificate I presented at the DMV wasn’t the original (I’d been careless there, too, bringing it with me to college and probably tossing it out when I moved) but a certified copy that the attendant reviewed skeptically before allowing me to pass. I was there in the first place because my license had expired during the pandemic closures, and I’d been given a grace period to figure it all out. It was humbling, for a very small moment, to have to prove who I was and that I deserved to be here. And appropriate, in a week where the Supreme Court defended DACA, to think about how much a piece of paper might influence one’s destiny. ** When I travel, I wear a money belt tight and low around my hips, my passport, credit card and any cash tucked inside there. I follow the rule of never leave anything important in the hotel. This was tested once when we had a 11 a.m. checkout from our hotel in Rome and returned from a visit to the catacombs at about 11:10 a.m. to find our belongings in the trash. (No problem—we dug them out and went on our smelly way.) And I also follow another rule: never put anything important in your backpack. Once, waiting for a bus in Barcelona, someone unzipped my backpack and went through it while I stood there oblivious, alerted only when the bus driver stepped in, yelling at the thief. My backpack held only a map, sunscreen, and a water bottle, all of which were still intact. Another time: Will and I were on a night train from Zurich to Paris, dozing uncomfortably in our bunks with our backpacks tight around our limbs so they couldn’t be pulled away when we slept. Suddenly, the door to our compartment opened and there were uniformed men with flashlights and German shepherds barking orders to us. Passports! Present your passports! It was like we’d fallen asleep and woken up in Nazi-occupied territory. Wordlessly, we dug in our money belts, handed over our passports, and stared at each other. Now what? We’d spent weeks guarding our passports with our lives, only to hand them over to the first people who demanded them. What exactly would we do if we arrived in Paris for our flight back to San Francisco with no documentation? How did one get a new passport—at the embassy? How long did this take? How did we prove who we were without the appropriate paperwork? It wasn’t until we crossed a border at some point the next morning that our passports were returned to us, and we finally felt safe again. Apparently, it was part of the process—an identification check—and not some kind of anomaly. We hadn’t been signaled out; everyone else in every other compartment had had the same rough awakening. Still—it took a while for my heart rate to get back to normal. ** After walking 764km to Santiago de Compostela—minus the meseta, of course—I would stand in line for an official piece of paper, fold it carefully and tuck it into my backpack, and someday not be able to tell you where exactly it was—a box high in my closet? A pilgrimage is meant to be spiritual, a mark on the heart.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Paula Treick DeBoardJust me. Archives

December 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed