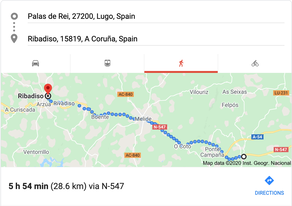

Palas de Rei to Ribadiso de Baixo (25.6km/16 miles) is a walk through the province of Galicia—white wine country, known for its el pulpo (octopus) and torta de Santiago (almond cake)—which has a heavily Celtic cultural influence dating to the 5th century. The countryside is dotted with horreos, raised wood or stone structures on pillars that used to house grain. The towns are small, the landscape rural. Ribadiso is not even a village—just an albergue surrounded by fields. This stage of the journey is marked by heavy crowds. At this point, we would have been two days from Santiago and four days from home. At this point, I’m four days from finishing my blog. ** We’ve been doing a little project at Casa de DeBoard—a landscaping design for our front yard, which we’ve been mostly ignoring for the better part of seventeen years. It has a rose bush I’d like to pull out, some non-exciting shrubs, a box hedge, and a large weed patch that we call a lawn and have faithfully watered and mowed just so the neighbors don’t hate us. The new plan calls for us to rip out all the grass (… goodbye, weed patch!) and put in stones, bark, and drought-resistant native plants, meant to grow in ridiculously hot and mostly arid climates. The process has revealed how very little I know about plants, but it’s been interesting, too—each plant I google has a history, can be traced back to so and so’s arrival in the New World. It’s funny to think of plants being carted halfway around the world, how the colonizers really just wanted to pick up the Old World and move it with them to their new place, like they were loading up a U-Haul and carting things across town. Maybe wherever we go, we want to protect ourselves from change. ** I like to think that the people who walk the Camino—a spiritual walk, following ancient paths—are well-intentioned, that they leave light footprints on the places they have visited and come away changed by the experience. But I’m on some Camino Facebook groups, and I see complaints about people leaving behind their trash on the walk—notably, toilet paper—but other things, too. There are people who bus their way through the Camino, stopping in small villages for stamps in their passports and overrunning local cafes before getting back on the bus. And then there are the complaints from disgruntled travelers: about the owners of albergues, the quality of the pilgrim meals, all the little things that didn’t meet their expectations. ** I wonder what it would be like to live and work along the Camino route, to come into daily encounters with pilgrims—weary and crabby and overwhelmed or loud and festive and obnoxious. Like any tourist-centric economy, people make their living from the pilgrims who pay to stay at the albergues, eat their food for first or second breakfast, make demands to arrive late and leave early and be accommodated at all hours. There is a sense of entitlement that sneaks along, packed into a tiny pocket: I arrived late at the albergue and the owner was grumpy and didn’t want to let me in! Well, duh. I suppose the owner wanted some sleep, too. I have been, as a traveler, hyper-aware that the people who serve my food couldn’t afford to eat in the same restaurant. (I know I don’t have to travel outside of my city to experience this.) I’m aware that there’s a role I’m playing: the entitled traveler, but also the person who is pumping money into the system that allows my server to pay their bills, feed their family. It’s not an easy balance. ** A few days ago at the grocery store, the woman behind the register thanked me for wearing a mask. She was wearing one, too—for an eight-hour shift, presumably, while I was just dashing in for… and here I will sound like the most entitled person in the world: a cup of quinoa needed for my turkey meatloaf. “It’s not a big deal,” I said. She smiled at me—yes, you can see that, even in a mask. The mask means you have to look a bit closer, actually look people in the eyes to have an interaction. “For some people,” she said softly, glancing around the store, “it seems to be.” This has become, weirdly, a dividing line in society. It seems like such a strange hill to die on (maybe literally). In the past, I didn’t think much about the little droplets of air expelled each time I breathe or talk or laugh, but these days I imagine them landing on the arm of elderly person, on the gallon of milk that will be picked up by a young parent and brought home. If we can tread lightly, I think we should. It’s not a difficult way to exist in the world.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Paula Treick DeBoardJust me. Archives

December 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed