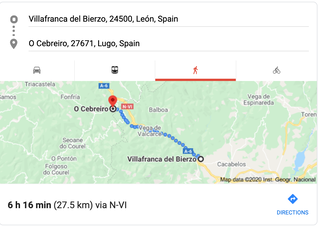

Today would have marked the 2/3 point of our journey: a steady, sweaty climb from Villafranca del Bierzo to O Cebreiro, at just about 30 km (18 miles). The ninth century stone village of O Cebreiro is “an impossibly quaint hobbit hamlet” that “smells like wood fires, manure and pilgrim B.O,” according to Rick Steves (who in 20 years of travel has never steered me wrong). At this point, pilgrims have exited Leon and entered Galicia, encountering another new language: Galego, a mixture of Spanish and Portuguese. There are seven more days until Santiago de Compostela; a good part of the journey behind, and a good ways to go. I read some blog posts from other pilgrims about today’s journey, and one woman described utter exhaustion setting in only halfway through the route: every time she saw a town in the distance, she thought it was O Cebreiro. It had to be; she’d been walking forever; she had nothing left. But it wasn’t, and she had no choice but to keep going. There’s no way to know what your own journey will be like, even with a roadmap. ** Sometimes when I look back on the person I am today, versus the person I was five years ago or ten or definitely twenty, twenty-five years ago—I don’t recognize the older versions of me. Things are about to get personal here. This is your warning to leave. ** For a long time, I allowed other people to define things for me—and that included defining me, who I was, what I could do. I was in my thirties when I raised my voice for the first time (not literally; but almost literally), when I thought that I might have something to say that was worth the effort, when I broke free from the things that had been holding me back. I’m talking vaguely. I can circle a topic for hours; watch out. How to say this? I grew up in a community where a woman’s highest calling was to be a mother. No problem. I figured that was coming down the road for me at some point. I had a mother. The women I knew were all mothers. It was so expected it was taken for granted; women who didn’t have children were anomalies, oddities, eccentrics. And then, when I was 13 and experiencing such heavy cramps and bleeding I was in the doctor’s office repeatedly, I first heard the word ‘infertility’ mentioned in connection with me. The doctor said the word to my mother, maybe judging that I wouldn’t know what it meant or that I was too young to be part of the conversation. But I knew the church-word for this: barren. It was never once presented as a positive thing for a person to be. Over the years, despite medications and painkillers and lost days each month and thousands of dollars in emergency care bills, my condition grew worse, and when I was 22, I had an operation that made infertility no longer a possibility but a fact. For a decade, I drifted. I went to everyone’s baby showers. I learned how to knit an eight-hour baby blanket (--full disclosure: it takes me twice as long, but that’s the name of the design.) I spent my time around people whose conversations revolved around their children’s milestones, parenting techniques, homeschooling. It was in many ways a loving and generous environment, but the span of the communal embrace wasn’t wide enough to include me. I don’t mean this as an indictment of anyone else’s behavior. When I look back on those years, I see myself as the outsider who just didn’t have the guts to get out. It was hard to fit into the group. I had to use my elbows to claim a little space, and it exhausted me. I kept doing: knitting, baking, trying to find my way to that common experience. But I had different interests, different ideas. I was teaching, I was reading, I was studying. Looking back, I’m sure I exhausted them, too. It wasn’t until I went to grad school that I finally made my exit from the circle. In a way, it was terrifying. Those were the people I knew and loved, even if we didn’t understand each other, even if we had different vocabularies. I didn’t know where I belonged, who I was when I wasn’t trying to camouflage myself. But also, of course, it was a relief. I became a person who wasn’t defined by a deficit, but by the qualities I did have and the things I could do. The process of becoming, like leaving the cocoon, has to be painful and terrifying at times—otherwise, you haven’t really come that far. ** In many ways, I’m the latest of the late bloomers. It took me a long time to figure out who I wasn’t, and then who I was. It took me a long time to learn that I could speak, that I had a right to speak, and that maybe there was even some value in what I wanted to say. It’s so funny to me that as a teacher, I feel I can recognize this in students so easily, this thing I couldn’t recognize in myself for so long. Here’s a person who needs a little nudge. Here’s a person who is afraid. Here is a person who might need a word of encouragement to start on this path. ** How long did it take you to write your first book? I’m sometimes asked. There are practical answers, like a year of the first draft, another six months for a second, other revisions at later points. But also, a more honest one: 37 years.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Paula Treick DeBoardJust me. Archives

December 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed