|

A year in reading (since it wasn’t a year for much else)

1. Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narrative Craft by Janet Burroway (For my fiction writing class. One of the best books on craft around.) 2. The Best American Short Stories 2019 ed. Anthony Doerr 3. Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimimanda Ngozi Adichie (Brilliant, horrifying, heart-breaking. There’s a scene in here that will stay with me forever.) 4. The Things We Cannot Say by Kelly Rimmer 5. The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood (A re-read. I was planning to start the Hulu series, and I wanted to remember what I’d read so long ago.) 6. Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors and the Drug Company that Addicted America by Beth Macy (For my freshman comp class. It was amazing the research questions they came up with based on this text.) 7. Unspeakable Things by Jess Lourey 8. The Care and Feeding of Ravenously Hungry Girls by Anissa Gray 9. Bury Your Dead by Louise Penny (Who doesn’t love Chief Inspector Armand Gamache?) 10. My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh (I didn’t love this as much as Eileen, but it was in the same weirdly brilliant way.) 11. The Immortalists by Chloe Benjamin (One of my faves. The premise is brilliant, and these people broke my heart.) 12. Followers by Megan Angelo 13. The Only Woman in the Room by Marie Benedict 14. Landline by Rainbow Rowell (Audiobook. Charming, lovely, kitschy in the best way.) 15. The Female Persuasion by Meg Wolitzer 16. The Other Mrs. By Mary Kubica (My second favorite in Kubica’s line-up.) 17. The Hired Man by Aminatta Forna (A quiet book that stuck with me in a lot of ways. It looks at the aftermath of war, and asks what we do with our wartime misdeeds and everyday criminals, especially when those people are ourselves.) 18. The Nest by Cynthia D’Aprix Sweeney 19. Jar of Hearts by Jennifer Hillier (Audiobook. A dark thriller.) 20. Miracle Creek by Angie Kim 21. Husbands and Other Sharp Objects by Marilyn Simon Rothstein 22. A Friend of the Family by Lisa Jewell 23. A Ladder to the Sky by John Boyne (I officially have a crush on John Boyne.) 24. State of Wonder by Ann Patchett (Ann Patchett can make me interested in things I didn’t know I was interested in. Just damn good story-telling.) 25. Exit West by Mohsin Hamid 26. He Said/She Said by Erin Kelly 27. Wilder Girls by Rory Power (I read this for the social-distance-this! book club. This was back when the pandemic was going to last for just a month or so.) 28. A Duty to the Dead by Charles Todd 29. Code Name Verity by Elizabeth Wein 30. The Warehouse by Rob Hart 31. Pretty Things by Janelle Brown 32. Marlena by Julie Buntin 33. Recursion by Blake Crouch 34. Truly Devious by Maureen Johnson 35. Everything Here is Beautiful by Mira T. Lee 36. An Impartial Witness by Charles Todd 37. My Dark Vanessa by Kate Elizabeth Russell (another read for the social-distance-this! book club. Dark indeed. I admire how the author let the main character stick to her guns, even though as a reader/woman I wanted to scream for most of the book.) 38. A Bitter Truth by Charles Todd 39. Father of the Rain by Lily King (I’d read Euphoria and was fascinated by it. This is a much more familiar story, but the characters are well drawn.) 40. The Vanishing Stair by Maureen Johnson 41. The Road to Jonestown: Jim Jones and Peoples Temple by Jeff Guinn (I felt like this could have been trimmed 150 pages or so, but it was a pretty exhaustive look at the cult.) 42. Wild Game: My Mother, Her Lover and Me by Adrienne Brodeur 43. Sometimes I Lie by Alice Feeney 44. A Good Girl’s Guide to Murder by Holly Jackson (Unexpected surprise for me. Smart and edgy.) 45. An Unmarked Grave by Charles Todd 46. The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas (Long overdue read. Should be required reading for high schools.) 47. On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous by Ocean Vuong (for social-distance-this! book club) 48. A Trick of the Light by Louise Penny 49. Dominicana by Angie Cruz (I found this on a “what to read instead of American Dirt” booklist, and it was a compelling immigrant coming of age story.) 50. Stay With Me by Ayobami Adebayo (I’m in love with Nigerian fiction, and this was a fantastic read that truly felt universal.) 51. Conviction by Denise Mina 52. This is How I Lied by Heather Gudenkauf 53. Born a Crime: Stories from a South African Childhood by Trevor Noah (Recommended reading.) 54. There There by Tommy Orange (Excellent.) 55. The Dearly Beloved by Cara Wall 56. Sister Dear by Hannah Mary McKinnon 57. The Arrangement by Robyn Harding 58. The Nickel Boys by Colson Whitehead (Timely and convicting. A read for social-distance-this! book club.) 59. Writers & Lovers by Lily King (Audiobook. So damn good. Read Lily King!) 60. The Subway Girls by Susie Orman Schnall 61. A Gentleman in Moscow by Amor Towles 62. Darktown by Thomas Mullen 63. Stranger in the Lake by Kimberly Belle 64. White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk about Racism by Robin DiAngelo (A read for the Friday-night-anti-racism book club. Required reading for white people, like me.) 65. Dear America: Notes of an Undocumented Citizen by Jose Antonio Vargas (reading for freshman comp. My students loved this.) 66. One Day We’ll All Be Dead and None of This Will Matter by Scaachi Koul 67. The Island of Sea Women by Lisa See (read for the social-distance-this! book club. Had no idea this world existed.) 68. American Like Me: Reflections on Life Between Cultures by America Ferrera (Lots of great essays here, very teachable.) 69. Passing by Nella Larsen 70. Godshot by Chelsea Bieker 71. Alexander Hamilton by Ron Chernow (I read this with the Penguin-Read-Along. Pretty fascinating, lots of stuff not included in the musical.) 72. How to be an Antiracist by Ibran X. Kendi (Read for the Friday-night-anti-racist book club. Required reading.) 73. Blank Klansman: Race, Hate and the Undercover Investigation of a Lifetime by Ron Stallworth 74. Lost Children Archive by Valeria Luiselli (This didn’t quite do it for me, but it brought me to 75. Tell Me How it Ends, which was great.) 76. My Sister, the Serial Killer by Oyinkan Braithwaite (Darkly comic, delves into cultural and familial expectations. What wouldn’t you do for your sister?) 77. Fleishman is in Trouble by Taffy Brodesser-Akner 78. The Night Swim by Mean Goldin 79. Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup by John Carreyrou (Fascinating. Good companion to the Netflix documentary Inventor: Out for Blood.) 80. The Sun Down Motel by Simone St. James (True crime fans, unite!) 81. The Gunners by Rebecca Kauffman (I loved this so much, I shot a five a.m. book review video.) 82. Such a Fun Age by Kiley Reid 83. The Great Believers by Rebecca Makkai (In the top ten for 2020, for sure.) 84. Maybe You Should Talk to Someone: A Therapist, Her Therapist and Our Lives Revealed by Lori Gottlieb (Read for a Writing for Psych class—part memoir, part-therapy. Recommended.) 85. The Last Flight by Julie Clark 86. Long Bright River by Liz Moore (Gritty, dark police drama.) 87. Red at the Bone by Jacqueline Woodson 88. Mexican Gothic by Silvia Moreno-Garcia (Wild and inventive, a great gothic read.) 89. Tell Me How it Ends: An Essay in 40 Questions by Valeria Luiselli (Highly recommended.) 90. Maid: Hard Work, Low Pay, and a Mother’s Will to Survive by Stephanie Land (Read this instead of Hillbilly Elegy.) 91. The Witch Elm by Tana French 92. These Women by Ivy Pochada 93. One Drop: My Father’s Hidden Life—A Story of Race and Family Secrets by Bliss Broyard (read for Friday-night-anti-racist book club) 94. American Prison: A Reporter’s Undercover Journey into the Business of Punishment by Shane Bauer (Undercover look at private prisons. Completely horrifying.) 95. A Place for Us by Fatima Farheen Mirza 96. The Whisper Man by Alex North 97. The River by Peter Heler 98. The Bright Lands by John Fram 99. Ask Again, Yes by Mary Beth Keane (Heart-breaker. Just a good story.) 100. Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead by Olga Togarczuk

0 Comments

Because I’m telling you this story, I can start and end it wherever I want. I can focus in on something that happened in the middle or leave out the middle entirely. I can skip the boring parts (like the hours I spent responding to emails or grading student responses). I can decide that this is a story that doesn’t need an ending and essentially leave you, the reader, hanging. Also: I could lie. I could tell you fantastic things that make my life much more exciting than it is in reality. In the vein of true crime, I could invent a villain and have him (her?) arrive in the dark of a very early morning, standing just over my shoulder. (There was no villain.) I could make myself the hero of this story, in the classic sense of the word. I came! I saw! I conquered! I could suggest my own benevolence, all the ways my mere presence made the horse farm a better place to be. And just like that you would feel sorry for me (a villain!), proud of me (a conquering hero!), delighted by me (a wonderful human). This is the power that comes with being a writer. ** But I may as well say that on the second morning, I took about two steps off the deck and without warning, without my brain kicking into slow motion to process what was happening, my left leg shot out in front of me and then somehow I was on the ground with that leg twisted underneath me, small bits of gravel digging into my skin. Will, to his credit, waited until it was clear nothing was broken to laugh. (And it was funny—or it would have been if the fall didn’t cause an ankle-to-knee bruise by that evening.) I’m 44, not 80, so there was no fractured hip, and we were alone except for a few horses, so the embarrassment was helpfully contained. I picked myself up, brushed off my pants, and we resumed walking. “How did that happen?” I kept asking, and Will kept logically replying that the flagstones were slick, that I’d hit some stray gravel and lost my footing, but this answer was deeply unsatisfying. What I meant was, how could something like that—so potentially harmful, with the power to derail our whole mini-vacation—happen to me right at this moment when everything was supposed to be lovely and pristine, when the entire day was stretched out before us like a new life we could sample and decide to keep? ** We drove into Monterey with LG sitting on my lap, the throbbing on the left side of my body dulled by a generous dose of ibuprofen. It was a weekday during a pandemic, and so there were only a few masked people walking on Cannery Row, plenty of parking on the streets. In Pacific Grove, we pulled right up to our old favorite park on the peninsula and wandered between yogis and dog walkers and tide poolers. I took a picture of Borgs Motel on Ocean View Boulevard—a bit of a family inside joke—and sent it to my Treick group chat. We decided it had been a long time since we’d been on 17 Mile Drive, and so we paid $10.50 and drove past towering homes hiding behind their gated entries and cypress trees and Bird Rock, which was covered with hundreds of gleaming, squirming seal bodies, their cries echoing back to shore. There was nowhere to be and no time at which to be there, so we stopped at the mile markers that looked interesting, with LG straining on her leash to sniff out the inhabitants of every hole in the ground. I kept getting hit by realizations—that feeling, again, that life had gone on without us, the surreal idea that maybe the pandemic had only been in our minds or had only, somehow, happened to us. When we met another person on a walking trail, I searched their faces—the inch or so of visible skin between sunglasses and the top of their mask—for signs of how their lives had been disrupted, for clues as to how they kept going. The next day, we drove in the other direction, north to Santa Cruz. We hadn’t been in years, maybe because Santa Cruz was a vivid part of our pasts and its memories belonged there. Will used to bomb over to the coast in his ’93 Plymouth Sunbird convertible whenever he had a chance; I spent a summer working in the Santa Cruz mountains when I was 19. (Our lives overlapped for one single morning during that time, when I went along with a friend to meet Will for breakfast. A year or so later, when I was back in Iowa, he reached out via email, and that was the beginning of this life.) The Boardwalk was more weathered than I remembered it, although it was always just this side of seedy. The parking lots were empty, weeds sprouting from cracks in the asphalt. We stopped at a beach on the north side, in a neighborhood that was too upscale to have been part of my teenage memories and walked down the steps to the water. (One night I remember vividly from that old time: being at a party in someone’s upstairs apartment, the beer flowing, and a guy I’d never met me interrogating me about how I could possibly live in the Valley. What do you even do there? he wanted to know. How do you even live?) On the beach, we had the feeling of being small in the face of something immense: waves crashing, birds feeding, a seal bobbing in the surf, rocks being worn away bit by miniscule bit. Business could fail and our health care system could be stretched to its limits and all the other structures we thought we could depend on could turn out to have serious cracks in the foundation, but the ocean was still here. The ocean was telling us we were idiots. We had dinner outdoors at an Italian place on Seabright, with LG in her mesh backpack on a chair next to us being perfectly quiet and well-behaved until she let out a tremendous, high-pitched yip that momentarily stopped all conversation.

And then we went to Marianne’s, the incomparable ice cream shop on Ocean Street, although we were already stuffed on meatballs on gnocci. I used to go Marianne’s every week with a few scraped-together dollars and call it dinner; the last time I was here, one of the guys I was with had an altercation with a stranger and punched him in the nose, drawing blood. I remember throwing away my ice cream cone unfinished and standing outside while police sirens approached, promising myself that this didn’t have to be my life. I didn’t have to always choose the jerks. There was no indoor seating at Marianne’s now, of course, so from the sidewalk we watched the employees joke and move around behind the windows, and then we got back into the Mini, drove across the street, and parked facing the road, ice cream dripping down our chins as we ate. Twenty years ago, this was my life. Now it felt like I was getting a rare glimpse of something extraordinary, inching apart a closed curtain to see what was there. I used to be a person who was adventurous. It’s hard to remember that sometimes. When we arrived at the horse farm, I became the Paula-equivalent of a roly-poly bug curling into itself: I put on warm clothes, plugged my phone into an outlet near reach, and sat on the couch with my knees pulled to my chest. It was the farthest I’d been from home in more than seven months. Since March, I’ve only filled up my gas tank three times, although that used to be a twice-a-week routine. The most recent time, I pulled into my regular gas station only to realize it had changed brand, the pumps new and shiny, the numbers on the digital display all visible. It was like an episode of the Twilight Zone. The world went on without me, but all the time I was right here! A few months ago, back in the early stages of the Year of Our Pandemic 2020, my friends and I wondered how this experience would change us as people. Let me admit: I wasn’t sad to think that handshakes with strangers, let alone hugs from strangers would be gone—those were never my things. If people always stood at least six feet from me in the grocery store, I could probably die happy. But it didn’t occur to me that I’d be scared to merge onto the freeway. Or that I’d have a (mini) panic attack on a perfectly safe little horse farm just because I wasn’t tucked away in my own home. ** Things at the horse farm looked better in daylight—the horror movie sheen had worn off, and all the creepy shadows and sounds became daily life on a working farm. From the kitchen window where I stood sipping coffee, I could see a woman in the paddock in knee-high boots, shoveling horse patties into a wheelbarrow. The dogs—three of them, one possibly an Australian shepherd charged with keeping horses, humans and other animals in line with energetic barking—dashed past the window. Two of them got into a play fight and tumbled over and over each other on the lawn, nipping and howling in faux-protest. I leashed up LG, and we walked the perimeter of the property, past the stables and the round pen, past the guest house where we were staying and the main house with its Porsches and Audis lined up neatly in the driveway, around the track for show jumping with its brightly colored obstacles, past a pond with some ducks that quacked at our approach, near the chicken coop (with LG tucked into my shirt, so as to prevent her from getting any ideas), through rows of grape vines covered in netting to protect them from birds before the harvest, and finally back to the paddock, where a horse watched us silently from the fence. Things were looking up. I could get used to this, I thought. We drove to Moss Landing and walked onto a state beach that was deserted except for a few surfers, paddled far out into the blue. (LG is okay with sand but wants nothing to do with the sound of crashing waves.) We kept the windows down and let the salt air sting our noses. At night, we had pizza and beer on the deck with my nephew, who drove up from Monterey. We talked about Covid and cults (highly recommend The Vow, y’all) and various trips we had taken, and at one point the whole sky to the east lit up with fireworks: the Dodgers had won the World Series. Later, we heard coyotes howling—first one from somewhere off beyond the gated entrance, then another answering from the farm next door, where earlier I’d seen a worker gathering what looked like the end of the summer squash from a field. A mosquito found my neck and perplexingly, the back of my knee encased in my pandemic-tight jeans, and it was time to call it a night. There was a clunk in the middle of my dream, a sound that seemed close and therefore relevant enough to drag myself back to consciousness. It’s a farm, I reminded myself. There are noises that happen on a farm. And thankfully, it’s not your farm, so none of those noises concern you.

I thought about the things that used to scare me at my grandparents’ farm—the loose floorboards in the hayloft, the squeals of a cow whose head was stuck between bars, the pitchforks and other potential weapons hanging from their pegs on the walls. Nothing there had killed me either. In the morning, I went into the bathroom and found that the shower door had come off its tracks and was dangling precariously over the chasm of the tub. ** Another time, probably but not definitely before the shower door slid off its hinges, Will whispered into the dark: “Do you hear that?” I hadn’t been hearing anything except my own brain—for once, mercifully quiet—and so I blinked myself awake, concentrating. It was the same howling we heard on the deck the night before, but louder now, as if the coyotes—wolves? is the difference important?—were circling the house. And still, somehow, I fell back asleep. Will and I (and a somewhat nervous LG) got away for a few days. Here’s how it happened: First there was a global pandemic and all our huge and carefully constructed travel plans for 2020 disintegrated into nothing. Then, I kept myself very busy doing everything I could think to do around our house—a complete overhaul of the front yard, replanting in the back yard, updating the linens for our bedroom, repainting the interior and exterior house trim. The other day, with 30 minutes between my class Zooms, I took everything out of the refrigerator, wiped down the shelves, and put everything back in more or less exactly the same place. While I am a slightly anxious person under the best of circumstances, these are not the best of circumstances. It’s possible I’m going crazy, I told Will that night, after the refrigerator incident. And so we started looking for Air BnBs near the coast. The drive to the horse farm was windy and at times one-lane, and although the Google Maps app was mostly a champ, there were times when it was clearly playing catch-up, and “turn right in a quarter mile” became a second later the sputtered command to turn right NOW. The sun was just setting when we passed the entrance to the horse farm and made our way up a remote path until we could turn around. We only had a glimpse of the place by the time we hauled our bags inside and the sun set entirely—vineyards on either side of the driveway, horse stables and a long row of white fencing nearer the road.

The darkness, when it came, seemed absolute. Will and I tried to order dinner from a Mexican restaurant in the nearest town, but the website wasn’t working, and so he set off into the dark. LG and I settled in like doomed characters in a horror film. It was bright and cheerful enough inside the little house—bedroom, bath, a functional kitchen, a small living area that had been carefully shot in online photos to seem like a much larger living area. The problem was that it was bright inside and dark outside, and there were no curtains to pull over the many windows. I tried the blinds, which seemed to be circa 1980, although a decorator could pinpoint that more accurately, and succeeded in moving one half of one blind six inches before abandoning the quest. The uneven blind drooping in the window drove me crazy, but I didn’t dare trying to even it out for fear the whole thing would come crashing down. Please send me updates, I texted Will, who was probably just past the gate. And then I sat back and waited to die. Well, not really. But I did clutch LG and think, what the hell am I doing? I could be in my own little house where everything is where I want it to be—no fruitless search for a trash can, for example—surrounded by the comfort of my things—a warm blanket, fifteen different streaming services, the rows and rows of my books. (There is a cabinet with books here, and although my inner snobbishness instantly raised its head, they are decent books: Elizabeth Strout, Amy Tan, Larry Watson, some full-color art books, Lean-In by Sheryl Sandberg.) I picked up my phone and scrolled through it—Amy Coney Barrett had just been confirmed by the Senate—and set my phone down. I came to escape all of that. I came to escape myself. ** In the morning, I’m up before the sun—but not much before. I send an email. I work on a flier. I think about opening my manuscript—the last time I worked on it, Sunday morning, I made a major change that scares me a bit—but don’t. I boil a pot of water and unpack my French press—I’m not reckless enough to leave coffee to chance—and sit down at the kitchen table. There is a small, fattish spider crawling up the wall three feet from me, and I have not yet crushed it. Have I become a different person, living (for 12 hours now) on a horse farm? There is evidence of other critters, besides the horses—two dogs, one (heartbreakingly and too, too soon) a beagle mix, at least one cat that has driven LG to craziness, something that was potentially under the bed, where LG was very curious to sniff, and some ants that seem to emanate from a bowl of fruit on the table. (For some reason, every time I have typed “horse” it has come out “hourse”—hours? House? What’s happening here?) It’s getting lighter, and I can see a horse in the paddock (I have no idea if this is an accurate word) outside the kitchen window. It’s time for a muffin and another cup of coffee and the beginning of this day. Also the spider has disappeared, which means it could be anywhere. We’re (I’m?) repainting our bedroom. My husband may be wondering if we didn’t just do this; we did, but it wasn’t just. Time only seems that way sometimes. It was five years ago, and that’s about my limit for things looking and feeling the same. Also everything else in life has changed in five years, so why shouldn’t the décor? ** Back at the beginning of the pandemic, after the initial mad grocery-store panic and when we had entered the hopeful, honeymoon phase—long walks with friends, adventures in cooking, binge-watching—Will and I wondered how this experience might change us. Would we become better versions of ourselves—healthier, thinner, more centered? Would the fact that the world had come to a screeching halt remind us of what was important in life? I remember seeing a picture of blue skies over a major metropolitan area (maybe it was Los Angeles) and thinking this was what our world needed: a reset. Let the smog dissipate. Let the animals roam. I don’t have a name for this phase, months later, but the honeymoon has long been over. This morning when my alarm went off, I grabbed my phone and scrolled with blurry eyes through social media posts (the president has Covid, or doesn’t but says he does, depending on whose post I was reading), then set the phone down and tried to remember what day it was, what I needed to do. Writing, dog walk, meeting at 9, look at my lesson plans for next week, send an email about such-and-such, read for book club tonight, paint the bedroom ceiling.

Yesterday I did the harder part, standing on a stepladder and inching my way around the room, cutting in with the ceiling paint. It’s the same color I painted the ceiling in my living room two years ago, which in my tendency to hyperbole I nicknamed The Brightest White in the World. While I worked, I listened to an episode of The Murder Squad from earlier in the year (remember life before the pandemic?) and heard the guest, a woman, describe how she had entered her DNA into GED Match and that helped nab a killer who happened to be a distant relative. I stabbed the brush into a corner, smearing it with paint, and realized I was jealous. Why couldn’t I have a grand purpose? Why was I so bored (stuck? depressed?) that the best way to handle it was to repaint over a perfectly decent paint color? But this morning, even in the almost complete darkness of five-thirty, I looked up at the ceiling. I could see where I’d cut around a light fixture—it will take an electrician to remove this thing, and to replace it with the ceiling fan I want—where I’d taped off the smoke detector, the gaping hole where I’d removed the vent cover. The new paint was that same brilliant white I’d fallen in love with two years ago. Next to it the old paint looked off-white, the color of a dirty bath towel. It’s not a grand purpose or anything, but in less than twelve hours, I will have the white ceiling of my dreams. Tomorrow I’ll wake up and that part of the project will be done (or done-ish, because there’s still the matter of the ceiling fan I haven’t ordered yet), and I’ll be happy. (Happy-ish.) ** Earlier this week, a student showed up to my Zoom office hours, ten minutes late for his fifteen-minute appointment. He was quiet when I asked where he was with his essay. “When I made the appointment, I thought I would be further along,” he admitted. “I thought I would have something to show you.” “That’s all right,” I said. “Why don’t we just talk about it?” I could hear the relief in his sigh. It’s a small blessing to understand that we don’t have to be perfect, that we don’t have to live up to our own expectations. It’s one step at a time, it’s bird by bird, it’s one brush stroke after another. ** One way or another, we’re going to get through it. (Right?) It’s 6:40 a.m. and I’m in my writing spot with a giant cup of coffee that reads: COFFEE PAIRS NICELY WITH SILENCE. (Who got me this mug? It’s so me.) I’ve sent two emails and looked at a ceiling fan I might buy even though summer seems to be finally, finally over. I read a FB post from my local newspaper and skimmed through the comments and steeled myself to not say anything. It took incredible willpower, and my husband would be proud.

This is today, and I am here for it. ** Or, I am mostly here for it. Put another way, I am not altogether here. ** Right now, it feels like a very hard time to be alive in the world. I’m not trying to be dramatic—I wasn’t the one who wrote the plot about pandemics and fires and smoke plumes and hurricanes and forced hysterectomies and whatever else is happening. (Are murder hornets still a thing?) And it’s mostly quiet in my little world—I didn’t have to flee my home or batten down the hatches. We did put our beloved beagle to rest last week, something that would have happened with or without fire and pandemic, but has left us nevertheless with a barren landscape. Since March, I’ve been teaching and writing from home. There was an immediate contraction of my social circle when the pandemic hit—no bumping into acquaintances in line for a mojito at the State Theatre; no squeezing into the last two seats at the Prospect; no nodding hello to the sweet older couples at church. I miss all of them. I miss passing my colleagues in the hallway and bitching about an email so-and-so sent. I miss the woman who made my skinny vanilla lattes twice a week and talked to me like we were old friends. (And I’m such a shit, I can’t even remember her name.) I miss little things seeming like big things. Now it’s only big things, and there are so many that they have started to feel like little things. ** How do we do it? How do we put one foot in front of another when it seems like nothing good will come of that path? (I’m using we, but maybe it should just be I. Whatever this is, it’s experienced as a collective, but it’s also deeply personal.) I’ve been writing, but mostly blog posts that go nowhere, rather than the carefully crafted story waiting for me in a Word doc. That story is about a deep grudge that festers for fifteen years. In a way it seems too simple for right now, a revenge story for easier times. ** How do you write when the world is on fire? I mean that metaphorically, because the air right now is in the green (good) category—the best it’s been in weeks. (Fires are still burning, and people and animals and livelihoods are still being destroyed, but the wind, for now, for my corner of the world, has shifted.) I know this because I consulted first my weather app and then what I call the doomsday app, which always predicts higher temps and a higher AQI. I’ve begun to average the two together, suspecting one is too optimistic and the other too pessimistic, and that the truth lies somewhere in the middle. That’s where I am, stuck between extremes. I have the French doors open; my eyes and nostrils aren’t tingling from smoke, and little flakes of ash aren’t falling like snow. I can breathe. I’m alive. I can try this again tomorrow. It’s 6:19 and ungodly quiet in my house, except for the hum of my refrigerator about four feet away. I’m writing in the “dining room” (our house is too small for this to be said in anything other than air quotes), where I’ve been writing since the third week of March, the beginning of taking the pandemic seriously in CA. This was the same time our beloved beagle began his final downward slide—so slow then that it wasn’t absolutely certain it was coming, unless you believed in reality and science, and 2020 hasn’t been the year for that.

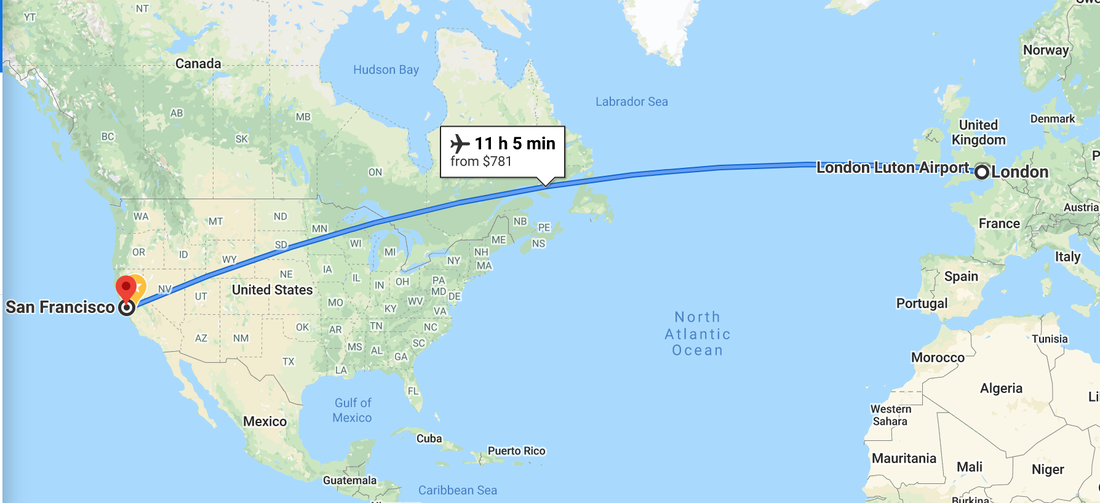

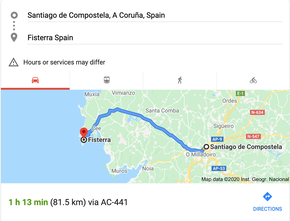

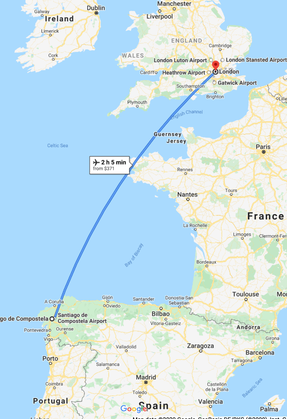

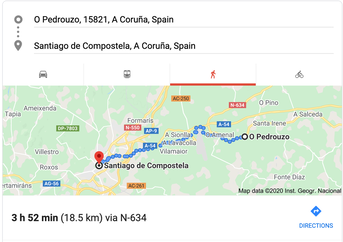

I initially set up shop here because this table is far from the bedroom where my husband would sleep for another hour or so, and because of the proximity to coffee, and because as he got older, Baxter’s bladder seemed to get smaller, and I could lean over and open the French doors to let him out to the yard and five minutes later back in again, in a more or less continual cycle. I did this daily for almost seven months. After a week, these mornings quickly became a pattern. I did my writing here, my quick morning skim of social media, my patting of the sweet dog who lumbered past, down the steps and out into the yard. But we brought Baxter to the vet for the final time on Tuesday, and now it’s Friday, and there’s no reason I can’t carry my cup of coffee to the room specifically set up to be my writing room. The lighting is better there, and there’s no constant hum of the refrigerator. LG, our rat terrier, is a late sleeper, and no one needs to go in and out of the French doors. (It’s blissfully cool outside, but the air quality index is in the unhealthy range from nearby fires, and the door—all doors, all windows—must stay closed.) And yet I can’t move. There’s a story hovering at 68,000 words that needs my attention, and I can’t open the document. I know what this is, the heavy weight on my chest, the purposelessness. It’s grief. Even when I’m not directly thinking about B, I’m noticing the way our lives have changed. I came home from the vet’s office and gathered all of B’s things—his bed, his water bowl and leash, his shoes (really, he didn’t have many things)—and carried them out into our garage. Now our hallway, where he slept on the hardwood during the warm nights and in his bed on the cooler ones, is empty. We bought LG a new water bowl, one I will fill once a day instead of a dozen—toward the end, B drank long and hard throughout the day, reacting to the heat or his own natural thirst or maybe because he’d forgotten he drained the bowl five minutes earlier. There is no longer a four-times-a-day medication schedule to keep, and anyway those little orange cylinders have been tucked away, out of view. Part of the grief is the consciousness of these thoughts, the guilt lurking right behind them like a shadow. B was almost a full-time patient at the end, needing help to stand and go outside or come back up the porch steps. My life, it is true, is easier now. My floors, without B’s drips and leaks and daily accidents, will be consistently cleaner. I have slept, three nights in a row, for more than six hours at a stretch. And yet the house is unbearably quiet. There are no toenails clacking on the floor, no sounds of panting next to the oscillating fan, no one lapping up water from a stainless-steel bowl. This newness is my life now, and it doesn’t seem to fit. I wish I could have the noise back, the messiness. I wish he would distract me in the middle of a sentence, so that I would have something to grumble about when I returned to the screen. I wish I could even open that document and write one lousy sentence, but I’m not there yet. I’m here, in the quiet.  Today we would have flown from London through Toronto to San Francisco, then BARTed to Pleasanton, then been picked up by some dear willing soul and ferried back to Modesto, either passed out in the back seat or so keyed up from travel caffeine that we couldn’t stop telling stories. The end. (And thus, today: the end of this #TheOtherCamino blog.) ** Today, the news that COVID-19 cases are spiking all over California has led to speculation that we’ll be sheltering in place again, that in fact the urge to reopen was premature, and our careless gatherings have proved that the virus never went anywhere—it was just waiting for us to let our guards down. I’ve been at home—minus some neighborhood walks, trips to the vet with a sick beagle, grocery runs, a trip to an abandoned airfield and an ill-advised recycling run where my tin cans netted me 23 cents—since March 12. Last week, my fall 2020 teaching schedule was confirmed, and it looks like I’ll be teaching my courses from home. I’ve gone through something like the stages of grief with this realization: denial, anger, bargaining, depression. I’m not quite to acceptance yet. Home isn’t just the place where I crash after a long day—it’s now the place where I put in the long day. I can relax here, but more and more, I’m trapped, too. My story isn’t special—this is happening all around my city, state and country. It’s happening all around the world. Sometimes it gives me comfort to think of so many of us at home, staring at our screens, trying to reach out to each other in little ways: a text, a meme, a thumbs up. Sometimes it depresses the hell out of me. ** Over the last 28 days, I’ve discovered new corners of my 1,000 square foot space: I write in the mornings at the kitchen table with the French doors open and my beagle wandering through, looking for a spot for his nap; I Zoom from my office with my bookshelves in the background; I read in the warm afternoons sprawled across the bed. I’ve been trying to do subtle improvements: a new dish drainer, new suction shower hooks, a basket system for Will’s rolled-up t-shirt collection. (This has been my biggest accomplishment of 2020, other than writing a blog for 28 days in a row.) I’m trying to make peace with my home, and with myself in this space. ** Yesterday, I opened the side gate and let two friends into my backyard. One I haven’t seen since February, although we text most days, little check-ins to remind each other that we’re alive and we care. The other friend I had only met on Zoom in a weekly writing group, but talking for an hour a week for three months has accelerated our relationship. We’re friends now, compatriots, kindred spirits. It’s been the unexpected joy of this pandemic. We sat in the backyard with coffee and tea, spaced apart, moving our chairs and the umbrella to avoid the sun. And it was hot. This was a commitment to friendship, to humanity. We were determined to sit six feet apart and just be together. This is all we have right now, and it has to be enough. ** If you’re reading this blog, thank you. Thinking in such a focused way about this walk, I’ve felt more attuned to the idea of the journey, and the people on the journey with me. We have each other, and that is enough. ** Since the beginning of 2019, when we started talking seriously about walking the Camino, Will and I (but especially Will, who’s quite good at this) have been seeking out other pilgrims who made the journey in previous years. We pumped them with questions, and they gave us their best advice: skip the meseta or stay in hotels every now and then or buy the right shoes. They told us what food was good and what food wasn’t, what kind of walking sticks we needed, whether we should continue on to Finisterre. Every single one of them said the trip was worth it, and most that they would do it again if they had the chance. Writing this blog has been bittersweet: it’s kept me adrift during this month of no other plans and at times heart-wrenching loneliness, but it’s also made me hunger for this trip. This is a journey I want to take someday, when the world rights itself. #Camino2021?  Santiago de Compostela to Finisterre and back (bus, 81km each way). Santiago de Compostela to London (plane, about 2,000 km). Many pilgrims leave Santiago de Compostela and do one last walk: to the Atlantic Ocean. Finisterre (from Latin finis terrae) was so named because in Roman times, it was considered to be the end of the known world. It’s a three-day walk, or roughly an hour by bus. There are three things pilgrims must do in Finisterre, according to Efren Gonzalez. (I’m linking his Finisterre vllog here, so you can watch it. We’re Efren Gonzalez fans around here. Fair to say, Will?) They are: -Take a dip in the ocean. -Burn something that’s been with you the whole way (like your clothes, or the underwear you washed every night in the sink for A MONTH). -Watch the sunset. Then, it’s said, the next day you’ll be a new person. ** We planned to do a quick trip to Finisterre by bus, then return to Santiago de Compostela for a flight to London, and then another flight the next day back to San Francisco. This would have been an end of the world/end of the journey kind of day. **  In that other, non-pandemic life where I would have been finishing the Camino with my husband and some of the best people we know in the world, this would have been day 27 without my dogs, the chaise lounge where I’m writing this, my laptop, cereal and television. I’m so firmly ensconced in my at-home world right now that it’s hard to imagine being gone long enough to miss it. These days, a trip to the grocery store still feels somewhat momentous, a little trepidatious. When I come back after thirty minutes, the dogs greet me like I’ve been gone for a week, and I feel compelled to report on the conditions, like I’ve been out on the front lines: “Hardly anyone in Winco at 9:30 p.m. on a Friday. Almost everyone wearing masks. Produce was pretty picked over, though…”. But if I had indeed been gone for 27 days, I would have driven my companions insane with my constant worries about my dogs—what they were doing, if they were happy, if LG was able to sleep without me, if LG was still eating her food, if they were already going crazy with pre-4th of July fireworks. Every single night, no matter how exhausted I was from the day’s walk, I would have had a difficult time falling asleep without LG’s nine-pound body tucked up against the back of my knees. I would have checked my email obsessively for mandatory dogsitter reports (I prefer the “proof of life” version with the dog holding the day’s newspaper). “The dogs are fine,” Will would have told me, approximately twenty-seven times a day. And twenty-seven times a day, I would have sniffed back some tears. ** Coming back from anywhere always seems to take twice as long as getting there in the first place. I’m not sure how much of this Will and I shared with our Camino traveling companions in advance, when we were planning our trip and buying our plane tickets, but he and I have had some uniquely bad experiences with air travel. We were once denied entry to a flight that our luggage had already been booked on; that was also the night we slept under a café table at Heathrow. We’ve had missed flights and delayed flights and rearranged plans—and it’s all fine, really. It’s part of the adventure. It’s just not that much fun when you’re exhausted, when you haven’t had a really good bath/shower in a month, and when you’re sick to death of the two clothing options in your backpack. About a decade ago, I chaperoned a school trip to Washington D.C. and New York: twenty-two 7th and 8th graders, me and my colleague Tu. During this week, I don’t think I got more than six hours of sleep a day, and each day was nonstop go-go-go. In the last twenty-four hours of the trip, we bused from DC to New York, walked all over Manhattan, went to a Broadway show, bused back to Brooklyn for only five hours of sleep, had an early breakfast, wandered around Ellis Island, and got on a plane. The second after I counted and double-counted and triple-counted to make sure everyone was on board, I buckled myself into my seat, leaned my head against the seat ahead of me, and fell into a dreamless sleep. The next thing I remember, it was six hours later, and Tu was shaking my arm and telling me we were landing soon. I’d slept through takeoff, food service, in-flight entertainment, and turbulence. And my neck was killing me. ** In 2002, after our month-long trip around Europe, we were beyond ready to be home, but we had to make our way back to Paris. Our last stop before the final train was in Zurich, and we had a few hours to kill before our train. “What do you feel like eating?” Will asked. The appropriate answer would have been fondue, or some sort of Swiss delicacy. Anything that you wouldn’t get in the States: that’s our rule when traveling. But the answer that shot out of my mouth was, “McDonalds.” And so, we ate that night in a three-story McDonalds with the most modern seating I’ve ever seen in a McDonalds, the whole restaurant pulsing with techno music. It wasn’t bad food; it had the requisite salt and fat contents to make it taste quite good. But the point, right then, was comfort. The point was that we wanted to be home, that we missed even the crappier aspects of home. It’s good to set out on a journey, but it’s also good to return. And that’s tomorrow.  The final stage of the Camino Frances is from O Pedrouzo to Santiago de Compostela. At 19.7km, it’s one of the shortest days on the route; because it’s the last stage, headed toward the place where all the pilgrims are converging, it’s the most crowded part of the walk. For those who started in St. Jean Pied de Port and walked straight through, it’s been a 775km (481 mile) journey. Those who skipped the meseta (that would be my group) were looking at 482km (299 miles). Either way: that’s a hell of a long walk. Santiago de Compostela is the (disputed) site of the tomb of St. James (yep—the apostle James from the New Testament). Since the Middle Ages, pilgrims have been traveling (on foot, mostly) to visit the Catedral de Santiago de Compostela. With its baroque façade and Romanesque bell towers, it’s impressive even if you aren’t Catholic, and even after you’ve passed roughly a hundred churches along the way. Upon arrival, travelers queue outside the pilgrim office to get their official Compostela, the certificate that proves the pilgrimage happened—something that will presumably last longer than blisters and sore muscles. Maybe even longer than a blog post. Buen Camino, the typical greeting of pilgrims on the trail, translates to good road or good path. It’s an acknowledgement of a shared sense of purpose, an understanding and respect for another person’s journey.

The last time I was in Spain (which is a funny way to say it, as if I’m in Spain all the time)—we went to Pamplona and Will did the encierro, the running with the bulls. There’s a traditional costume for the run—a white shirt, white pants, a red scarf around the waist and a red handkerchief around the neck. (The white represents San Fermin’s purity; the red represents his death by decapitation. You don’t have to dig far into tradition to find the blood and gore.) The streets are full of runners in these costumes; the clothing marks them, gives them a sense of camaraderie. After his run, when his head was so inflated he had to duck through the doorways, Will was part of this group. His heart was still pumping overtime, adrenaline not yet settled. Every time we passed another person in white and red, they acknowledged each other with a solemn nod. Solidarity. We survived. ** Santiago is lively: here’s where you meet up with the people you passed along the way, where you get your Camino souvenirs and (ill-advised?) scallop-shell tattoos. There’s a guy playing bagpipes in the cathedral passageway. Many people stay in the Parador, a famed five-star hotel—a definite luxury after bunkbeds and communal living. (“Would we have stayed in the Parador?” I asked Will. He laughed. “I can tell you damn well we wouldn’t be staying in an albergue.”) There’s something celebratory about being in Santiago de Compostela, for sure—but also, something bittersweet. It’s the end of one journey, the beginning of another. ** If the walk changes you, then who are you at the end? What will you do with yourself? How will you take your changed self back to the real world? The truth is, writing this blog has more or less saved me from a deep Camino-shaped depression. Back in March when the pandemic hit and shelter in place became mandatory, I threw all my focus into figuring out remote teaching. I had to rethink some curriculum, learn different ways to deliver information, and stop teaching at times to be a counselor, a cheerleader, a person in my students’ lives who cared. While the Internet was full of witty memes and suggestions about how to spend the time in quarantine—I was swamped, so tired some nights that I dragged myself to bed before ten. And then, abruptly, the semester ended the first week of May. I did my grading. I cleaned the house. I tackled a few neglected projects. I kept moving to keep the weight of the trip I wasn’t going to be taking from settling onto my chest, like an X-ray apron. The summer of doing nothing and seeing just about no one, trapped mostly in my house during long strings of one hundred plus days loomed on the horizon, an unbearable possibility. “I think I might do a little blog about our trip,” I told Will. “What trip?” “The one we’re not taking.” “Huh,” he said. ** I don’t do a lot of personal writing. (Or I do, but it’s disguised as fiction.) My own life has never struck me as particularly interesting—just comfortable—and I worried that I wouldn’t have the material to keep this going. No problem, I thought. I’ll write about our pets. I’ll write about Will. I’ll write about the Camino itself. It’s been like a little puzzle to figure out every day, finding the edges and corners, filling in the middle. It has been its own kind of journey. ** It’s said that the walk changes you, but I think it must also be true that the walk changes everyone in a different way. That’s another mantra of the Camino: no two Caminos are ever the same. Put another way: everyone walks their own Camino. |

Paula Treick DeBoardJust me. Archives

December 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed