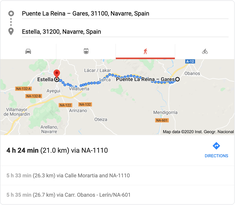

Puente la Reina to Estella is a 20km hike, mostly through little towns: Mañeru, Cirauqui, Lorca, Arandigoyen, through vineyards and olive orchards. When Will and I were first paying attention to COVID-19, in the first week of March, we saw the news of the outbreak in Italy, the horrible death toll, the overwhelmed hospitals and morgues. I remember that we were sitting in front of the television, and we looked at each other. Well, shit. Although we held out hope, expressed in odd moments during the early stages of our quarantine--maybe the virus wouldn’t be as bad as the early reports, maybe it would clear up soon, maybe travel would be possible after all—it was soon clear we wouldn’t be heading to Spain on June 1. In fact, the Camino groups we follow online were issuing clear and urgent warnings: If you are here walking, stop now. Make your way out of the country. Go home. If you are at home—stay there. Do not come. Travel restrictions soon followed: “Only Spanish citizens or citizens/legal residents of EU or Schengen countries may enter Spain. U.S. citizens without Spanish/EU/Schengen citizenship/residency likely will be barred from entering or transiting Spain by air, land, and sea.” As of June 6, there were 241,310 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Spain and 27,135 deaths. 490 deaths were in the Navarre region, where we would have walked today. Health care workers have made their own protective equipment, and nursing homes have been overwhelmed. (See source.) This is no time to be a tourist. ** There are two ways to go through the world: as a traveler or as a tourist. I’ve been both. I’ve been the tourist who hits the highlights of a city in a day or two and returns home with a few trinkets in a suitcase, a basic understanding of geography, a few snapshots of customs and cultures, a shallow understanding of people and place. In 2002, Will and I were making our way from Venice to Rome via train, when we ran into an American couple about our age. At this point we’d been traveling for a couple weeks, and we’d had very few full conversations, due to our limited guidebook phrases and the fleeting nature of our encounters—friendly wait staff, harried news agents. We immediately started chatting about where we’d been and where we were going, and about five seconds later, I realized I disliked these people intensely. It wasn’t just because the man kept referring to the Pantheon as the Parthenon, as in “I hear you can walk right into the Parthenon as long as they aren’t holding a service.” I gritted my teeth, whispered “Pantheon” under my breath. It wasn’t just because the woman was asking if I knew where to find Prada, where the best shopping was. At her feet were several crisp paper bags bearing the names of high-end designers, the contents wrapped in tissue. At my feet was my grubby backpack bearing two changes of clothes, my travel journal and the novel I would rather be reading. At the train station, we parted ways, but the next day, there they were: arguing in front of the ATM near the Pantheon, their angry English soaring over the busyness of the square. I linked arms with Will and pulled him the other way before they spotted us, toward a fountain alive with splashing children and a nearby gelato cart. I have thought of these people often over the years. It’s easy to be scornful of them, easy to judge with very limited knowledge of their situation and only this small snapshot of time. And also I’ve worried that I’ve become them—I have a larger bank account than I did eighteen years ago, and maybe I’ve become somewhat jaded as a traveler: been there, done that. ** A tourist sightsees, skimming the surface of the locale; a traveler digs in to experience the culture, the customs, the food, the people. A tourist has no understanding of the place, and therefore leaves without it making a deep impression on them. Oh, Rome is great. There’s a fantastic Prada on Via de Condotti! A traveler wants to understand, to visit places beyond the Ten Things to Do In… list. A tourist blusters into a new landscape, looks around, finds fault with the way the landscape is different from what they expect. A tourist speaks boldly in their native language, passing judgments, wanting to educate others, needing to be heard. The traveler is quieter, an observer rather than a doer, a listener rather than a speaker. A tourist has the answers--the guidebook provides them—even if they are superficial and incomplete. A traveler uses the guidebook as a starting point, but does their own investigation, talks to the people who live there, hears from others who don’t share their perspective. ** I have been a tourist in my own country, too—in my own community. I have not always investigated, not always dug deeper to understand the history, to find the truths or confront the lies. I know this is privilege: I can make it through life without too much unpleasantness. I can sit back and be shocked that people are angry, that anger can turn violent. It is easier, although too deeply unsatisfying, to be a tourist. It is more challenging, but deeply rewarding, to be traveler.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Paula Treick DeBoardJust me. Archives

December 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed