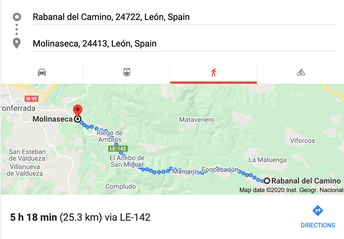

The walk from Rabanal del Camino to Molinaseca—25km—gets to the highest point of the French Way (1515km) and then begins a long descent. It’s one of the most important days for pilgrims, as it includes the Cruz de Ferro (the Iron Cross). It’s basically just that—an iron cross on top of a five-meter wooden pole, possibly erected as a landmark for pilgrims, although its disputed history has it being constructed by ancient Romans, the Celts or St. James himself. It’s a reflective place with stunning vistas: from there, you can ponder how far you’ve come and how far you have left to go. The Cruz de Ferro is surrounded by small rocks carried by pilgrims from their homelands. When a pilgrim leaves a rock, it’s symbolic of leaving a heavy burden behind. ** On a very literal level, I am from a rock family. I don’t know how many people can truly say this, because I have no idea how many people collect rocks, display them, show off their latest finds like a good report card. When I mentioned my family’s hobby to a friend of mine in grad school, she said, “I literally have no idea what you’re talking about. There are people who do this?” I nodded. There are indeed. My family collects rocks. My family knows something about the geology of the rocks they collect, and also has an aesthetic appreciation for what is an interesting rock and what is just a… well, a rock. As a result of this interest, my family has spent quite a lot of time combing rocky beaches in rather chilly locales, walking the wrack line, stuffing the pockets of our windbreakers. The worst thing you could do to my parents would be to plop them onto a sandy beach with no rocks or shells to discover. Our vacation collections might get pared down, but still, a significant amount of rocks come home from each trip and end up in decorative bowls, or on mantels. It’s not unusual to visit my parents’ house and hear a rock tumbler tumbling away in the garage. It’s also not unusual to visit their house in March, after their annual trip to the Arizona Rock and Mineral Show and be expected to listen to detailed descriptions of their latest acquisitions: a stunning piece of tanzanite, a glittery geode. I should mention that I didn’t inherit this rock gene, and that a good portion of the time when I’m with my family, I have to fake it. Fortunately, I married a guy who knows about rocks, and he picks up the slack for me. (However, it was somewhat alarming to see, when Will and I moved into our first apartment, that he had brought some giant hunks of obsidian with him.) ** Over the years, I have conceded to allow various rocks into our married existence, and I’ve even found myself picking up the odd stone here and there, zipping it into the pocket of a backpack where I might encounter it months later. What is this? Why do I have it in my backpack? We have a small display of stones next to our record player (see picture), including these personalized ones from our dear friend’s wedding in Wales. (Now that was a rocky beach.) But these are the rocks we’ve collected from various places in the world, and not necessarily the home rocks a pilgrim might carry to the Cruz de Ferro.  Each May, after a busy semester during which I promised myself repeatedly that I would get the backyard in shape bit by bit and then proceeded to do nothing at all out there—I embark on a yard project. This requires many gallons of water, multiple audio books, various lawn implements and a lot of physical labor. There are winter leaves lurking under bushes, spring weeds sprouting in the middle of the lawn, trees that should have been trimmed months ago, bermuda grass that has gained a foothold in the flower beds. Each May I dig and toil and develop a startling flip flop tan and halfway through tell myself I should just give up, hire someone else to do it. But then I look around and realize I’ve made some progress, and I keep going. Inevitably this process upturns some stones—tiny pebbles, surprisingly hefty ones that feel, when the spade first hits it, like I’m striking a long-buried bone. I’ve begun to collect them—it’s possible I did inherit this gene, after all—in a flower pot, these little treasures from the earth, working their way to the air. I would probably have brought one of these backyard stones with me to Spain, just a small one to not weigh down my pack, an unassuming one, a humble one. A very Modesto kind of stone.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Paula Treick DeBoardJust me. Archives

December 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed